By Michael T. Wood, Guest Contributor

On 20 July 2015, the United States and Cuba reopened their embassies in Havana and Washington, D.C. This occasion represents another important step in the normalization of U.S.-Cuban relations, and continues a policy shift that began in December 2014. Even though more action is needed on both sides of the Straits of Florida, no one can deny the historic nature of these events. In light of these changes, it seems like a good time to explore an often overlooked or misunderstood portion of U.S.-Cuban sport history: American football in Cuba.

Before I continue, since this is my first post, I will start with an introduction. My name is Michael Wood and I am a doctoral candidate in the Department of History and Geography at Texas Christian University. Over the past few years I have taught sports-related courses as an instructor for the Department of American Studies at the University of Alabama. My research focuses on American football played between U.S. and Cuban teams from 1907 to 1956. In this piece, I will present a brief overview of the sport’s history in Cuba, discuss its place in the current historiography, and explain the approach I take in my dissertation. But first, I will address some misconceptions about games between U.S. and Cuban teams.

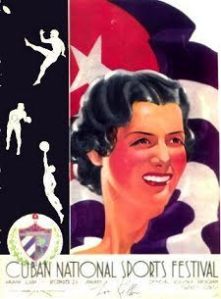

Program for Cuba National Sports Festival, December 1936-January 1937. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Auburn University Libraries, Auburn, Alabama.

The most commonly used name for games between U.S. and Cuban teams is “Bacardi Bowl.” Its Wikipedia page includes a list of ten games and a couple of brief summaries. I would consider this information misleading at best. There were far more games played between U.S. and Cuban teams, and they were not called Bacardi Bowls. Sportswriters and university administrators in the United States introduced that designation for the games after the fact in part to augment their programs’ bowl legacies. These contests would regularly be described as just exhibition games or international matches. Further, the University of Havana, Cuban athletic clubs, or the Cuban government financed the games, not the Bacardi family.

The 1937 Auburn-Villanova game in Havana comes closest to being a “bowl,” since it was held during the expansion of postseason play in college football during the mid-to-late-1930s. Organizers intended the game to become an annual affair as part of a national sports festival. The first contest scheduled two North American teams, but later games would feature U.S. and Cuban teams. The deaths of three Cuban Naval pilots on a goodwill tour in Colombia forced the cancellation of the 1938 game and plans for the future matches never materialized. Even still, American football games continued on a local level and between U.S. and Cuban teams until 1956.

Now, with the whole “Bacardi Bowl” issue tackled, what about the sport’s history in Cuba?[1]

Cuban universities and athletic clubs played American football for over 50 years. The sport’s history on the island predated the first varsity squad at the University of Florida by a year and Cuban elevens competed on the gridiron for more than twenty years before the founding of the University of Miami in Coral Gables. Members of the Vedado Tennis Club and students of the University of Havana fielded teams and held the first American football games in Cuba in 1905. Afterward, Cuban colleges and athletic clubs, particularly in Havana, organized amateur leagues and played against each other until the mid-to-late-1950s. The number of teams in the leagues and games played varied from year to year, depending on the condition of the clubs and political stability on the island. Generally, American football remained within the socially exclusive, racially segregated institutions of the upper-/upper-middle-class sport culture in Cuba.[2]

University of Miami vs. University of Havana football game, 25 November 1926. Courtesy of the University Archives, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida.

In addition to the local amateur leagues, international games took place on a fairly regular basis. From 1907 to 1956, U.S. and Cuban teams played approximately 52 games. These contests pitted squads from colleges and universities, athletic clubs, and military bases in the U.S. South against teams from the University of Havana and five Cuban athletic clubs. They took place in Havana at Almendares Park from 1907-1921, on the grounds of the Vedado Tennis Club in the 1920s, at el Gran Stadium Cervecería Tropical (La Tropical) and el Stadium La Polar de La Habana (Stadium Polar) in the late-1930s, and at the University of Havana’s University Stadium from 1923 through the 1950s. U.S. cities also hosted games between U.S. and Cuban teams, including: Tampa, Miami, Lakeland, and Orlando in Florida; Statesboro and Savannah in Georgia; Spartanburg, South Carolina; and Dothan, Alabama. And this is just from what I have been able to piece together so far. It appears clear to me that there is more to American football in Cuba than a few handfuls of games. There was sustained participation in Cuba and a consistent effort to hold games between U.S. and Cuban teams. This is without a doubt a subject that deserves deeper investigation.[3]

In the historiography, baseball and prizefighting overshadow American football because of their popularity and racial inclusiveness. Since American football was a sport played primarily within Havana’s social athletic club culture, it becomes marginalized or characterized as part of U.S. cultural imperialism. Paula J. Pettavino and Geralyn Pye briefly mention the sport in their 1994 book, Sport in Cuba. It appears as a minor sport on the same level as squash, judo, professional wrestling, and professional bodybuilding. In his 1999 book, On Becoming Cuban, Louis A. Pérez, Jr. touches on the subject of American football in Cuba while discussing the influence of North American sporting culture on the upper-class athletic clubs in Havana in the early twentieth-century. Gerald R. Gems expands on the subject in his 2006 work The Athletic Crusade. Similar to Pérez, he associates the sporting culture of the early Cuban republic with the upper-class. He writes, “Wealthy Cubans who had attended schools in the United States returned to their homeland and to establish the Havana Sports Club and the Vedado Tennis Club in 1902. Both eventually competed in baseball, basketball, and American football. The latter played against American colleges and the University of Havana, which eventually installed an American coach and an American athletic director,” and, “Early in 1910 a Havana team even defeated the Tulane University football team.” Gems links these events with other overt actions, such as the activities of the Havana YMCA, to Americanize the population of Havana and, with the number of North American victories on the gridiron, as a reinforcement of Anglo superiority. These three examples were just a sampling, but, in general, most scholars dismiss or only mention American football games between U.S. and Cuban teams as a minor point in support of a broader thesis. There are no in-depth academic studies that focus exclusively on the sport in Cuba.[4]

University of Havana football team, 1950. From: Vita Universitaria (September 1950). Courtesy of the Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida.

Given the amount of games played and the scant scholarly attention paid to them, I chose American football games played between U.S. and Cuban teams as a research topic, and hopefully my dissertation will fill a portion of this gap in the historical literature. To make the project more manageable, I decided to concentrate on games played between 1907 and 1933, but I intend to extend the study to cover 1934 to 1956. Using the model Michael Oriard establishes in his books, Reading Football and King Football, I treat accounts of the games from U.S. and Cuban newspapers and periodicals, student newspapers, universities publication, and archival materials, as “cultural texts” through which I examine class, modernity, race and ethnicity, gender, and national identity. Overall, I argue that American football held a comparable place in the U.S. South and in Havana, and that these games suggest that a transnational upper-/upper-middle-class sport culture existed between the United States and Cuba in the first half of the twentieth-century.[5]

In closing, the triumph of the revolution and ensuing changes doomed American football in Cuba. On 1 January 1959, revolutionary forces led by Fidel Castro toppled the General Fulgencio Batista regime. The new revolutionary government dismantled the existing Cuban sporting culture, which included banning the existence of exclusive athletic clubs, many of whom played American football. Broadly speaking, U.S.-Cuban relations quickly deteriorated after the revolutionary government nationalized North American assets. The United States retaliated with the passage of the Economic Embargo in October 1960 and the severing of diplomatic relations in January 1961. Tensions continued to rise with the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. Cuba became a flash point in the Cold War and the United States’ adversary in the Western Hemisphere. These events and others set U.S.-Cuban relations on a hostile path for the last 54 years.[6]

One of the questions I get asked frequently about my dissertation and research is, “Do you think games between American football will be played in Cuba again?” I would automatically respond in the negative. Despite the geographic proximity and the history of American football in Cuba, the cultural divide created over the past 50 years seems to be too much to overcome. But in light of recent events, I have adjusted my answer to, “It’s possible.” Perhaps unlikely, but once again the Cuban flag flies in Washington, D.C. and the Stars and Stripes flies in Havana. Who knows? Given the current climate in college football, the coming years may bring a real bowl game to Cuba, but I doubt Bacardi will be its corporate sponsor.

Michael T. Wood is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History and Geography at Texas Christian University. His research focuses on American football played between U.S. and Cuban teams from 1907 to 1956. He currently teaches sports-related courses as an instructor for the Department of American Studies at the University of Alabama. You can contact him at: m.t.wood@tcu.edu, michael.t.wood@ua.edu, or bacardibowl@gmail.com.

Notes

[1] Full disclosure: I use “Bacardi Bowl” in the title of my somewhat neglected research blog, “Bacardi Bowl: American Football and Cuba” (bacardibowl.blogspot.com). Perhaps it is a bit hypocritical on my part, but it is for the search hits. On a typical Google search, my blog appears on the first page of results, and it provides a little more depth than the other options. Also, it has given me the privilege to communicate with those interested in the subject. In the near future, I plan on revising and expanding it into a full website with more game narratives, roster lists, and profiles of important players, coaches, and officials.

[2] “El deportista,” Mella: 100 Años, Vol. 2 (Havana: Centro Cultural Pablo de la Torriente Brau, 2003), 214; Louis A. Pérez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 256; Alejandro de la Fuente, A Nation for All: Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth-Century Cuba (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 164. De la Fuente notes that the Cuban Amateur Athletic Union (Union Atlética de Amateurs de Cuba) excluded Afro-Cuban and mullatto membership through the 1930s. He mentions the existence of Liga Intersocial, made up primarily of Afro-Cuban athletic clubs. More research needs to be done to determine if these clubs played American football.

[3] According to my research, the list of U.S. teams (in alphabetical order) includes: American Legion (Tampa), Chatham Flyers, Florida Southern College, Fort Pierce, Georgia Teachers College (Georgia Southern University), Howard College (Samford University), Key West Naval Station, Louisiana State University (LSU), Miami Naval Training Station, Mississippi A&M College (Mississippi State University), Norman Junior College, Pensacola Air Base, Presbyterian College, Rollins College, San Antonio Air Base, Southern Mississippi College (Southern Mississippi University), Stetson College (Stetson University), Tulane University, University of Alabama (B-team), University of Florida, University of Miami (FL), University of Mississippi, University of Tampa. The list of Cuban teams (again, in alphabetical order): Club Atlético de Cuba (C.A.C.), los Dependientes del Comercio de la Habana (Dependientes), Havana Yacht Club (H.Y.C.), Policía (Cuban National Police), la Universidad de La Habana (University of Havana), Vedado Tennis Club (V.T.C.). These lists are by no means complete. They are based on what I have been able to piece together so far and do not take into account Cuban teams that did not play international games.

[4] Paula J. Pettavino and Geralyn Pye, Sport in Cuba: The Diamond in the Rough (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1994), 54; Pérez, On Becoming Cuban, 256; Gerald R. Gems, The Athletic Crusade: Sport and American Cultural Imperialism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2006), 89, 91.

[5] Michael Oriard, Reading Football: How the Popular Press Created an American Spectacle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); Michael Oriard, King Football: Sport and Spectacle in the Golden Age of Radio and Newsreels, Movies and Magazines, the Weekly and the Daily Press (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001). I use the approach to cultural imperial from Allen Guttmann, Games and Empires: Modern Sports and Cultural Imperialism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

[6] See: Thomas G. Paterson, Contesting Castro: The United States and the Triumph of the Cuba Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994); Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990).

My respects Dr Wood ,but what really amaze is that you call Batista government a regime ,which in some way is true,but then you call Castro regime “the new revolutionary government” ? WOW you sound very naive related to this .

LikeLike

Mr. Garcia, thank you for the comment. I appreciate the formal salutation, but I haven’t quite earned the title of “Dr.” yet. You raise an interesting point regarding the language we use when writing about the past. While words like “regime” can be somewhat loaded, that was not my intention in this case.

LikeLike

I was very surprised to learn that Cuba had such a long and old history with American football. As you stated this sport was mostly played at clubs amongst middle to upper class players, and was seen ‘as part of U.S. cultural imperialism.’ Was American football ever embraced as a major sport amongst the majority of the population in Cuba? I’m also confused as to why baseball is still so popular in Cuba. I realize your focus is on football in Cuba but I was wondering if you had any insight into baseball in Cuba. After all, baseball is known as America’s pastime, so why has it not been removed from Cuba’s culture similarly to American football as a part of US imperialism, and the government led dismantling of Cuban sport culture?

LikeLike

Thank you for the questions. American football never was embraced by the majority of the Cuban population. It remained a sport of the upper-/upper-middle-class social athletic sport clubs in cities, particularly in Havana. I recently found evidence of middle-class athletic clubs playing the sport too, but, according to my research and understanding, there was no widespread adoption.

Most academic works on Cuban sports, if they mention American football at all, describe it as part of U.S. cultural imperialism. One of the arguments I make in my dissertation is that the sport spread to Cuba organically and fit the pattern of diffusion of American football to the U.S. South, Southwest, and West. In effect, Cubans came in contact with American football in the northeastern United States and brought it back to the island. Perhaps that fits within conceptions of U.S. cultural imperialism broadly, but it seems to be consistent with the growth of what I call a “North American upper-/upper-middle-class sport culture.”

By contrast, baseball was much more entrenched in Cuban society. The diffusion of baseball follows a similar pattern to what I described above, but it entered much earlier and at an interesting time in Cuban history. I recommend reading Louis A. Pérez, Jr., “Between Baseball and Bullfighting: The Quest for Nationality in Cuba, 1868-1898,” The Journal of American History 81 (Sept., 1994): 493-517, for more explanation of how baseball served as a cultural form that distinguished Cuba as a new, modern nation from Cuba as a Spanish colony. Local, regional, and national amateur and professional leagues formed in the early twentieth century, with varying degrees of social and racial inclusion. The number of books devoted to Cuban baseball is too large to list here, but a good starting point would be Roberto González Echevarría’s The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

The best answers I have for why baseball survived the reorganization of Cuban sports and American football did not is that baseball had a longer history, it was more socially and racially inclusive, and it enjoyed more widespread popularity and participation on the island than American football. While Cuban baseball underwent reforms after the revolution, most of the institutions that played American football were disbanded and many of their members immigrated to the United States.

Hopefully this was helpful. Please let me know if you have any more questions.

LikeLike

I was interested in this article because I have always seen football as a primarily North American sport that was never really played outside of North America. I found it interesting how American Football began to pick up in Cuba around the same time that baseball and boxing were both the more popular sport of the time in both the U.S and Cuba. It was also interesting to see the amount of American football games played between the U.S. and Cuba just before the Economic Embargo era; seeing that both U.S. locations and Cuban locations were used for these international football games stood out to me as well. I have never really noticed American Football being played outside of North America, but seeing the amount of football games played in Cuba and the amount of Cuban Sporting clubs like the University of Havana that played American Football made me wonder why Football ended up banned in Cuba after the Economic Embargo.

LikeLike

Thank you for the comment/question. The best answer I have for why American football stopped being played in Cuba after the revolution, generally speaking, was that exclusive social athletic clubs were banned and most of the people who were members of those institutions immigrated to the United States.

LikeLike

First, baseball was not eliminated in Cuba because when Castro took over, baseball was an International sport played even in Japan and South Korea. not to mention Latin America. Football, on the other hand, was considered, only, as an American sport.

Football, by the way, was also played in Havana at the High School level. I played for the Instituto de la Víbora (Víbora HIgh School) back in 1947-48 just before it was terminated.

My father played for the Club Atlético de Cuba around 1930-32, They won the championship I think in 1932.

I have a newspaper clipping with a photograph of that championship team although it doesn’t say what year.

If the photo interest you, let me know.

Osvaldo J. Alfert, Sunrise, Florida.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comments, Mr. Alfert. I am interested in the photo and in learning more about your personal experience with American football in Cuba. If you would, please contact me by email (m.t.wood@tcu.edu; michael.t.wood@ua.edu; or bacardibowl@gmail.com) so we can exchange more information.

LikeLike

Pingback: American Football in Cuba: L.S.U. vs. University of Havana, 1907 | Sport in American History

Pingback: Review of Touchdown in Europe | Sport in American History

Mike. Great post and thank you. Just as an FYI. we secured the rights to host the Cuba Libre Bowl in Cuba in 2017. We would love to invite you to come down and be a part of it. Contact me at your convenience. Rob

LikeLike

Rob, thank you for the kind words. Please send me more information at my work address: michael.t.wood@ua.edu.

LikeLike

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History

Mr. Woods,

I would like to say thank you for sharing this interesting work. I am from Cuba and I belong to a generation that grew up without American Football (AF) in the newspapers or the TV. However, I love and I practice it actually. I didn´t know (I guess like a lot of Cuban people of my age or even older) that we had once AF matches on our island.

I don´t live in Cuba. I´ve never been to the United States. My first contact with the sport was in Brazil, but one of my dreams today is to be able to introduce Cuban people in practicing this interesting and spectacular sport. Your research is already contributing already to the possibility of celebrating an AF match again in Cuba.

Best regards!! Good Luck with the research!!

Eduardo

LikeLike

*Mr. Wood, correcting your name, sorry

LikeLike