By Kate Aguilar

The second thing people who understood Miami had in common was the realization that the real and the fake, the dream and the nightmare, the hope and the despair, were inseparable- that, in Miami, the good always came wrapped up in the bad.

~T. D. Allman, Miami: City of the Future (1987)

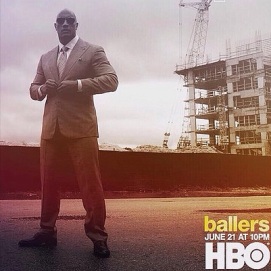

On August 23, 2015, the HBO football comedy series Ballers wrapped its first season. The show, starring former defensive tackle for the University of Miami Hurricanes turned professional wrestler/actor Dwayne Johnson, finished as the third most watched HBO comedy of all-time, behind Sex and the City (1998-2004) and the first season of Hung (2009). The reviews of the first season were mixed, with Variety’s TV columnist calling the show merely “‘Entourage’… with balls” in contrast to a review from The Hollywood Reporter summarizing the script as tossing “the pigskin with aplomb.” The latter focused on the work of Johnson, arguing his “multifaceted” approach kept the show “from becoming Entourage for athletes.” The former review contended the series, created and produced by alumni of Entourage (2004-2011) and focused on similar themes, “isn’t savvy enough about its subject matter to leave a mark.” Where one admired its poise, the other accused the script of failing to bring its “A” game.

Regardless, Ballers appears to bring a racially diverse group of mostly male actors to HBO who tackle issues endemic to professional sport, including the mismanagement of money, image, and time. Johnson stars as former Miami Dolphins linebacker turned financial manager Spencer Strasmore, who works for a White financial advisor named Joe (Rob Corddry). His all-Black group of potential clients includes Miami Dolphins wide receiver Ricky Jerret, played by Denzel Washington’s son John David Washington, and Omar Benson Miller as Charles Greane. Strasmore works alongside Jason (Troy Garity), a White agent, to help provide clients financial and moral guidance. The script explores how fame and fortune impact the lives of professional football players, especially when one or both has come and gone. While the comedy is admirable in its attempt, the presentation of such issues solely through the experiences of Black men is no laughing matter. Ballers must, in order to have game, pay careful attention to its game plan, or how it presents sporting culture through racial representation for mass consumption.

In the article, “Missing in Action: ‘Framing’ Race on Prime-Time Television” (2008), authors Meera E. Deo, Jenny J. Lee, Christina B. Chin, Noriko Milman, and Nancy Wang Yuen explore how televisual images “convey and infuse ideological meanings into societies” (p. 147). As they explain, television is a primary form of socialization that can and often does (re)inscribe racial difference. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall has written extensively on how such ideology informs practice, asserting:

How we “see” ourselves and our social relations matters, because it enters into and informs our actions and practices. Ideologies are therefore a site of a distinct type of social struggle. This site does not exist on its own, separate from other relations, since ideas are not free-floating in people’s heads. The ideological construction of black people as a “problem population” and the police practice of containment in the black communities mutually reinforce and support one another (p. 148).

We are not simply taught what or whom to fear, in other words, but shown it. The presence of “racial diversity” on television does not obscure how such persons are presented and thereby packaged for a mass audience.

Football, too, is not distinct from ideology. (“Ideology is a set of principles and views that embodies the basic interests of a particular social group” (p. 158).) [i] Presidents from Theodore Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan have used the game to define and showcase exemplary citizenship, positioning White men as the cultural ideal. Jeffrey Montez de Oca has argued football serves as a “technology of citizenship” where people in displaying their cultural competency assimilate into the body politic. Black men achieve the American dream by excelling on the gridiron, but even such excellence has yet to combat the limited leadership opportunities afforded to them off of it.

The characterization of the Black male as a “problem,” consequently, is historically linked to the ideologies surrounding citizenship and sport that most often reproduce the fit White male as hero. Susan Jeffords is but one scholar who has written extensively about the relationship between popular culture and “political theater.” “[She] contends that the ‘unified national body’ that Americans were seeking after the rudderless years of Vietnam and Jimmy Carter was configured in both blockbuster films and the Reagan White House as a masculine physical body – the hard body whose fitness, purpose, and courage could redeem the nation’s individual failures of will.” The action film during the Reagan years became a dominant form that celebrated White male heroic leadership reinforcing Reagan as the rightful commander-in-chief. With the exception of Rambo who is racially ambiguous, the heroes of these films were White men. Steven Spielberg films also ruled the era. Five of the top ten grossing films were either directed or produced by Spielberg and all focused on the reunification of the family under the direction of White males. Only one of the top ten grossing films of the decade had a Black male lead. Beverly Hills Cop (1984), starring Eddie Murphy, similarly underscored White men as more capable by presenting Black male characters as comic relief. While the interplay of Black and White men, anti-hero and hero, is not as readily available for public consumption through this HBO script, the limited representations of the Black athlete upholds this narrative.

Such ideology is also linked to and a product of the political strategy of “color-blindness,” a term popularized during the 1970s as a form of backlash political rhetoric against the demands of the Civil Rights movement. This strategy was sharpened under Reagan. “Color-blind” ideology repositioned “race-conscious” remedies like affirmative action and busing as the problem not the solution. Racial inequality in the post-Civil Rights Era has thereby manifested through social representations making the containment of “problematic” non-White persons no longer a legal right but a social responsibility. As a result, Reagan’s “welfare queen” from the South Side of Chicago could tread upon racial stereotypes conflating welfare, region, gender, and race without having to mention race overtly.

The power of this political language, which is still used today, is that it divorces race from historical context, making race an “accident of nature” not a product of political, social, and cultural developments. Since the use of racial classification to discriminate is now more carefully concealed, those who draw attention to racism become social pariahs or, as popularly called today, race-baiters. “Color-blind”’ politics, instead, celebrated catch-phrases like “diversity” and “multiculturalism.” These terms did not change the continual use of and references to Black caricatures in popular culture but made the deconstruction and eradication of racial difference more difficult. This form of representation under the guise of inclusion obscures the lived realities of non-Whites, which are much more complex and far more compelling. The show thus employs a diverse cast but Black characters in leadership positions, like the GM of the Miami Dolphins played by Dulé Hill, still garner little screen time and so fall flat. (In fact, this week during the 67th Primetime Emmy Awards, host Andy Samberg joked, “The big story this year is diversity. This is the most diverse group of Emmy nominees in history. Congratulations, Hollywood. You did it. Racism is over. Don’t fact check that.” The joke packed a punch, especially in relation to Viola Davis’ acceptance speech after becoming the first Black woman to win the Emmy for Best Lead Actress in a Drama Series, in which she explained, “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is simply opportunity. You cannot win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there.”)

Ballers is admirable, like Billy Corben’s documentary Broke (2012) for ESPN’s 30 for 30 series, because it employs a diverse cast and draws attention to the mismanagement of funds that plagues all professional athletes regardless of race or sport, especially considering the short time frame in which most athletes have to participate. Corben’s documentary, which aired on October 2, 2012, breathed life into a 2009 Sports Illustrated article of the same subject, entitled “How [and Why] Athletes Go Broke.” Sportswriter Pablo S. Torre revealed, “By the time they have been retired for two years, 78% of former NFL players have gone bankrupt or are under financial stress because of joblessness or divorce.” At the time, 60% of former NBA players were broke within five years of leaving the sport. MLB players were also not immune to economic hardship.

Broke was the result of Corben learning that former University of Miami quarterback Bernie Kosar, who later played for the NFL, had filed for bankruptcy, shortly after interviewing him for another documentary The U (2009). Kosar was a White player who as a quarterback in college and professional football epitomized the White masculine leader in sporting culture. Yet, in Ballers, a character like Kosar is nowhere to be found. The show takes an important look at why players go for broke: to achieve the American dream. It also explores how they go about doing so, but only through the experiences of Black men. In the Sports Illustrated article, though, Torres identifies risky investments, scandalous financial managers, divorce and infidelity, and a growing entourage as the primary areas that lead to money woes for all athletes. A lack of direction after football also contributes to economic and mental stress. Strasmore, we learn, was a product of financial mismanagement as his manager swindled him out of 800,000 dollars. Even as he strives to sign current players to protect them from this reality, we are aware that he hasn’t completely escaped his past. He, too, is financially strapped.

Money is not the only problem plaguing professional athletes; image and the issue of time, or the length of their career, also dominate the script. While Jerret, who is dropped from the Green Bay Packers in the pilot and eventually picked up by the Miami Dolphins, doesn’t have a money problem he does have an image problem. This problem, Strasmore warns, could make him unemployable and based on his spending habits perhaps broke. Jerret’s volatile choices lead him from a fist fight into a sexual encounter with a teammate’s mother, among other exploits. The script largely shows women as sexual objects; even Strasmore reminds his “friends” that women like cars are investments you should always lease. Greane, perhaps, combats this view as he is in a committed relationship and appears much more level-headed. But he, too, is tempted by the high-life and struggles to find his place, like Strasmore, in life after football. He eventually comes out of retirement.

The problem with such story lines is not necessarily that they don’t exist in professional sport – although one player commenting on the show scoffed at the idea of one teammate ever sleeping with another’s mother – but that they are not issues exclusive to the Black sporting community. The show is not wrong for showing such experiences in relation to some Black men. In 2014, Black players comprised 68.7 percent of the NFL. Still, 28.6 percent looked like Bernie Kosar. While a worthy discussion could be had on the designation of Johnson as Black due to his bi-racial descent and the role of Black advancement as shown almost exclusively through the light-skinned character, the reality remains. Black men in the show are largely depicted as “the problem,” even a level-headed Greane veers off track and must be put back in line by his wife. The leadership, in contrast, is primarily White: Strasmore answers to Joe, at first, and then Mr. Anderson; Jerret ultimately needs the approval of the White coach; Vernon Littlefield relies on the expertise of his agent. (Even though Joe, at times, makes rash decisions because of the allure of celebrity life, he is still shown as having options after leaving the firm because he has an education and has managed his finances well.) The result is to view the NFL’s vices – financial mismanagement, drug abuse, infidelity, prostitution, and domestic abuse, and crime – as Black problems, a fiction that the fact of Ben Roethlisberger’s history with women contests. The Pittsburgh Steelers’ quarterback, who is White, has twice been accused of sexually assaulting women; the concern over the resigning of Michael Vick in contrast to the silence surrounding Roethlisberger’s exploits highlights this double standard. Roethlisberger is, of course, but one example of White misconduct on and off the field.

Cover from “The Story of Little Black Sambo” (1899), a children’s book written and illustrated by Helen Bannerman. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps the most concerning caricature of Black men that the show draws from, however, is the image of the Sambo, or the perpetually childlike Black figure in need of adult White supervision. This mythology was used to defend White leadership and uphold the system of slavery and later racial segregation in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. While no character is overtly such caricature, it is notable that Strasmore berates Jerret more than once for acting like a child. (Littlefield is also presented as child-like and chastised accordingly.) Jerret, for example, gets into a fight with a Southern, White guy he refers to only as “Big Country” (itself an unfortunate stereotype). Although Jerret does not seek out the confrontation, he does not walk away from it. He is shown as acting on impulse without regard for consequence throughout the series. In fact, the only time he shows himself as a “man” is in confronting his absentee father who plays up this ideal of the Black man as either involved in fight or flight. The image of Black men as incapable of mental and physical control would impact other caricatures of and from the nineteenth century, including the Black brute, who was a social and sexual deviant. This ideology informed public practice in the mass lynching of Black men, which was condoned by political and popular culture.

Because of the relationship between ideology and practice, then and now, Ballers can and must do more. It is not enough to show Black men and their involvement in sport on screen; writers and directors must also challenge the stereotypes surrounding the culture, outcomes of an American history that has been far from colorblind. The show seeks to capture the desire for the American dream, and the pitfalls present for professional athletes in the uphill dash from rags-to-riches. In the process, it must beware of perpetuating racial nightmares. What we see matters; the continual reference to Black men as the problem, even if Strasmore attempts to be a part of the solution, colors how we understand football and those who play it.

The use of Miami to explore the landscape of professional football is an important choice for this show. The Dolphins, along with the Miami Hurricanes, have a storied football history. It is a city, itself, with a storied past and present as a result of Latin immigration and globalization. The city, some argue, shows the future of America, economically, racially, and culturally. The future of football, the show suggests, is also occurring here, as athletes like Strasmore parlay their time on the field into positions that allow them to advance because of it. This next generation of athletes seeks to become financial managers, agents, and coaches, among other roles. The importance of showing this complexity through the Sunbelt city of Miami cannot be understated. Still, just as these future leaders – the Strasmores – are not all White, neither are those struggling in and outside of the sport all Black.

In an interview discussing the impact of perhaps the definitive book on Miami, Miami: City of the Future (1987), historian and journalist T. D. Allman, explained that he chose the city because “[Miami] was where all the things creating a new America converged, so I first wrote an article for Esquire magazine… And then I wrote the book. The more I went into it, the more it seemed Miami truly was the city of the future.” Ballers, like the city in which it is set, may be the future of sports shows. A comedy to some, a dramedy to others that doesn’t shy away from the realities of professional sport, all the way down to using actual team names, players, and sports commentators on set. It may start a conversation that leads to real change. To have game, though, the script must also present the realities of the Black experience in and outside of football. It must recognize the tenuous relationship been race, masculinity, and representation that has historically played out on and off the football field. Some critics are right. The script as it stands is nothing new. Black men are the problem; White men, by and large, either are or help them find the solutions. But the show hasn’t been sacked yet. HBO renewed it for a second season. So, like Miami, who knows what the future holds.

Kate Aguilar is a Ph.D. candidate in History at the University of Connecticut where she studies racial formation, gender, sport, and political culture in the post-1945 U.S. Taking as a lens the University of Miami’s football team, the Hurricanes, her dissertation analyzes the central place of the sport and the city to the 1980s development of the New Right; a focus that makes evident the significance of the Global South and the diverse racial, national, and transnational histories of South Florida and the Caribbean to Ronald Reagan’s particular brand of conservatism and the masculine national identity it fostered. She can be contacted at katelyn.aguilar@uconn.edu.

Notes

[i]Meera E. Deo, Jenny J. Lee, Christina B. Chin, Noriko Milman, and Nancy Wang Yuen, “Missing in Action: ‘Framing’ Race on Prime-Time Television,” Social Justice, Vol. 35, No. 2 (112): 147-149.

I’ve never looked so in-depth at the characters being portrayed on television. I watch a variety of different shows simply for the entertainment aspect. I found this particular article extremely enlightening because it opened my eyes. It pushed me to analyze and question why this is the particular portrayal of Black athletes that seem to dominate the media and now a well-known network. The production still is what initially grabbed my attention and made me want to read the article. I thought to myself “I love this show… this would be a good piece to read for my blog assignment”.

During the first few minutes of reading, I thought why does this author have so many negative things to say about this series? I liked the Fact that HBO has a series with a predominately African American cast, illustrating what it’s like to be in the NFL as well as life after the NFL. Upon further review I noticed that each character is flawed in one way or another. Only one of the African American characters has a positive uplifting image as a head coach that put his own neck on the line offering a position to a hotheaded running back “Ricky James” played by John David Washington. Although as Kate Aguilar pointed out the positive head coach doesn’t get much screen time. I’m no sports buff by any sense of the phrase, but I know that in a sports industry that is made up of 68% African Americans total number of African American players being 1,155 many of which have went their entire career without making headlines and remain to be a positive role models for the community. It’s interesting that those depictions aren’t shown. I know drama makes for good ratings and entertainment but is it at the expense of holding this dark cloud of negativity over African American athletes?

What made you want to post this particular article?

Do you feel like the author as well as other people that have commented on the depiction of the characters highlighted in the series are reading to much Into the show?

Do you feel as though the cast evenly highlights a variety of different perspectives, or solely focuses on one?

Do you think HBO will consider expanding the cast to include a variety of story lines?

LikeLike

The main idea that was really thought provoking in this article to me was the opening quote by T.D. Allman, and how everything in Miami that is good will always be wrapped up in the bad. While the show Ballers is a great idea to emphasize the struggles that professional athletes have outside of their sport, I was really surprised by all of the racial undertones that were pointed out in this article. While there are many realistic struggles for professional athletes presented in the show, it does match the stereotypes that are becoming even more prevalent in our society today.

LikeLike

I was dragged into this article by the title, I saw “HBO’s Baller’s” and thought, I watch that show, I can read a blog post about it! However, never had I thought so in depth about the how the characters and the portrayal of black athletes might affect and set a precedent in society and entertainment. The blog quoted the recent acceptance speech given by Viola Davis in which she stated that you cannot win an Emmy for roles that are not there (referring to the lack of roles provided for actors and actresses of color). Even though ballers has a cast of primarily African American men, they do seem to be missing the point. It is not just about the opportunity for roles, but also what those roles portray. As I said at the beginning of this, I did watch all of Ballers season one. In reading this blog, I knew exactly what Aguilar was referring to, especially when she referred to the “Sambo.” It immediately clicked in my head that it was exactly what the show was doing, portraying these African American athletes as incompetent without the guidance of a higher power so to speak (the white men: agents, managers, coaches etc.). Were all of these aspects immediately apparent to you upon watching the show? Or did it take more introspection and thought for you to come up with this observation?

LikeLike

I like how you point out that the producers need to be more careful about how they label black male athletes in sports. The show ballers put’s a image in views minds showing that black males are not good with money once they reach stardom. I agree with you when you stated that not all black athletes are not bad with money. Some examples of this is Larry Fitzgerald he is a wide receiver in the NFL who is black that takes care of his financial situation very well, as well as a few other black athlete. Why do you feel that black men in America are targeted in society once they reach fame?

LikeLike

Trying to portray reality when it comes to professional sports can be a challenging task when it comes to dealing with stereotypes. This is sadly because of that fact that the stereotypes are there for a reason – a significant number of individuals fit that mold. The aim any television or movie producer should have is to convey that, yes, there are some who match the stereotype but there are others that do not. To be a truly responsible storyteller, you have to come at a difficult topic from multiple angles and not just tell the truth in some areas. As you mentioned – black players are not the only ones who act irresponsibly and get in trouble with the law. I lived in the Pittsburgh area for a long time so I heard about the Roethlisberger scandal plenty while it was going on. Most people quickly overlooked that, especially after he got married. This is not the case with Michael Vick as he is still very much hated for his past transgressions.

Unfortunately, I think that the fact that there are certain positions in football that are heavily dominated by one race or another help push some stereotypes. The last time I checked, most quarterbacks are still while and most running backs are still black. Do you feel that this contributes at all towards certain stereotypes and why do you feel certain races dominate those positions?

LikeLike

Being a white male college football player and having seen the show, I would have to disagree with your argument that the show promotes “Black problems.” Just because the black players have to answer to a few hire up “white” people does not prove any form of racism. 27 out of the 32 head coaches in the NFL are white and more than 75% of NFL team owners are white, so it would make sense for the character Jerret to have a white head coach who would indeed have the ultimate say in Jerret’s future. Do you not think that the show accurately depicts the life of some rookie football players who now have more money than they know what to do with and, as a result get into trouble with their newly earned wealth and fame? Like you said, a majority of the players in the NFL are black, but they are certainly not the only ones that get into trouble off the field.

LikeLike

I agree with what this article is saying. I believe it is unfairly portraying the way African-Americans are handling fame. They are only scratching the surface because the media (Like Ballers) shows only some of the players that are having problems. There are a lot of players in the NFL that are low-profile and don’t do anything against society. In the world of sports, they are predisposed to this stereotype. If you were 18, had no father, had a rough life, came from the inner city, and got drafted and overnight became a millionaire, wouldn’t that affect you? I don’t believe it has anything to do with race because I think money and fame would impact anyone hardly if they weren’t fortunate to have the privileges to know how to handle that type of spotlight.

LikeLike

I disagree with how they are suggesting that a television series is being stereotyped against male African-American athletes. What about the type casts of black men and woman that occur in modern day movies and television shows all the time? The NFL has over 67 percent African-American males and each of them display different characteristics and personalities. I feel as if this show is giving certain lives that this show displays a camera lens that we can see through and we as an audience can understand and grasp on to. They are young males that are displayed in this show and as a male, black or white, what would you do with a lot of money, power, and talent at such a young age? You might change your ways along with your character. People are looking too much into the racial aspect instead of the reality aspect. We see what occurs on the football field but what occurs when they get off?

LikeLike

Pingback: The Man in the Mirror: Black Culture, White Privilege, and Supermen in the Age of Cam Newton | Sport in American History

Pingback: From Superman to Just a “Boy”: Why a “Discussion” of Race, Sport, and Cam Newton Still Matters | Sport in American History