By Josh Howard

Our hope is that this exhibit inspires, educates and emotionally connects people of all ages…the remarkable story of the Negro Leagues. A lot of people say PNC Park is the best ballpark in America. Well, PNC Park just got a lot better. — Kevin McClatchy, then owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, speaking on Legacy Park, June 2006

This past spring, two statues depicting Negro leagues baseball legend Josh Gibson were on the move. In Washington D.C., the Nationals quietly relocated a Gibson statue along with two others to another section of their ballpark; in Pittsburgh, the Pirates tried to throw theirs away. Specifically, the Pirates gutted Legacy Square of its seven statues of Negro leagues ballplayers along with the associated interpretive panels. As Opening Day approached, the Pirates were set to destroy the statues after having already destroyed the large Legacy Square baseball bats. Purely by coincidence, Sean Gibson–great-grandson of Josh Gibson and Executive Director of the non-profit Josh Gibson Foundation–was offered a chance to rescue the statue of his great-grandfather. With insufficient storage or transportation, Gibson initially balked at the offer, instead suggesting the statues be redistributed throughout PNC Park, but once he realized the urgency of the situation, Gibson informed the Pirates that he would take the Josh Gibson statue–as well as the six others.

Legacy Square is technically still part of PNC Park of course, but it now looks very different, very empty, and very sad. Gone are the statues and the oversized bats, only to be replaced by simple banners depicting both Negro league and present-day Pittsburgh ballplayers. Further, speaking from personal experience, these banners are very easy to overlook. Legacy Square was originally designed to be a place to exclusively interpret and educate fans on Pittsburgh’s black baseball past, and that is quite simply no longer true.

What’s most shocking about the Pirates decision to purge local African-American history from PNC Park is that since the 1970s the Pirates have been leaders in embracing diversity within Major League Baseball (MLB). The Pirates were a bit slow to field a black ballplayer (1954, seven years after Jackie Robinson), but in 1971 the Pirates fielded the first all-minority starting lineup. So how does a franchise clearly aware of its past in a city with incredibly rich Negro league history simply remove the permanent exhibits of Legacy Square? Now that the Pirates season is officially over, perhaps the spotlight can be turned to these questions.

1988 to 2005

The odd thing about the Pirates’ modern-day Legacy Square actions is that, in addition to its 1970s diversity, the club was once at the forefront in acknowledging Major League Baseball’s role in segregating America’s sporting past. Toward the end of the 1988 season, the Pirates–led on the field by a young Barry Bonds and Bobby Bonilla–commemorated the fortieth anniversary of the Homestead Grays victory in the last ever Negro League World Series. A pregame ceremony honored living members of the Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the club raised a pennant banner for the 1948 Grays atop Three Rivers Stadium. The banner only remained for a week, but for that week the banner placed the 1948 Grays on equal status with the Pirates own World Series champions. Further, during the ceremony, the Pirates team president apologized for the role played by the Pirates and by Major League Baseball in perpetuating segregationist practices in baseball. Commissioner of Major League Baseball A. Bartlett Giamatti also spoke, saying of MLB’s role in segregation: “We must never lose sight of our history. Insofar as it is ugly, never to repeat it, and insofar as it is glorious, to cherish it.” (Rob Ruck, Sandlot Seasons, xvi).

With this moment, the Pirates became de facto leaders in navigating the complex relationship between professional sport and race, and this comparatively small ceremony was, at the time, a truly groundbreaking moment for professional sport in America. Over the next two decades, the Pirates continued what they started by holding annual Negro leagues nights and installing permanent Grays and Crawfords championship banners at Three Rivers Stadium in 1993. The Pittsburgh-area community embraced this past as well; most notably, the city of Homestead changed the name of the Homestead High-Level Bridge to the Homestead Grays Bridge in 2002.

Most MLB teams did not follow the Pirates’ example with large public events and apologies, but all engaged race in other ways: pre-game ceremonies to honor former Negro league players, the funding of inner city baseball programs, and, of course, the marketing of each respective city’s Negro leagues past in the form of throwback jerseys and ballcaps. By 2004, honoring black baseball history became formalized with MLB’s creation of annual Jackie Robinson Day celebrations for April 15. The Baseball Hall of Fame also revived the dormant Special Committee on the Negro Leagues Committee in early 2006 to enshrine seventeen players and executives for their contributions to black baseball. However, these efforts in the 1990s and 2000s came during a time when baseball executives fretted over declining game attendance, especially among African-American fans, not to mention public criticism of MLB’s declining numbers of black players, lack of black managers and executives, and total absence of minorities among ownership groups.But even with the most cynical of analysis, MLB’s acknowledgement of the Negro leagues had (and still has) great cultural importance, especially to the Negro leaguers themselves who were long discriminated against and then summarily ignored. As Hall of Famer and former Negro leaguer Monte Irvin stated in 1988, “I’m glad they are finally getting recognized, because 20 years from now most of them will be gone.”

2006-2014

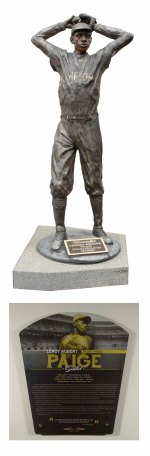

Returning to Pittsburgh, in 2006 the Pirates again honored the Grays and the Crawfords by presenting another major tribute to Pittsburgh’s Negro leagues legacy, this time in the creation of a permanent exhibit space in Legacy Square. Meant to pair with PNC Park’s statues of the Pirates’ Hall of Famers, Legacy Square included seven statues of the Gray’s and Crawford’s greatest ballplayers, individually honoring Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, Buck Leonard, Satchel Paige, and Smokey Joe Williams. Speaking to MLB.com in 2006, Sean Gibson expressed his amazement at the Pirates’ construction of Legacy Square: “We never thought anything like this would be created, this is a great honor.” Further, Pirates Owner and CEO Kevin McClatchy hoped Legacy Square would create a new spirit of historical engagement within the Pirates ballpark: “This exhibit inspires, educates and emotionally connects people of all ages to…the remarkable story of the Negro leagues. A lot of people say PNC Park is the best ballpark in America. Well, PNC Park just got a lot better.” Generally, baseball fans, historians, and the Pittsburgh community applauded the Pirates again for taking a leadership role in interpreting Negro leagues baseball.

Pirates owner McClatchy was out of the organization the very next year, selling the team to a group led by Bob Nutting. With McClatchy’s departure, it seems the Pirates abandoned their commitment to Pittsburgh’s sporting past as well as the education, empathy, and engagement hoped for by McClatchy. However, it’s worth noting that the Pittsburgh-area community continued to embrace the city’s Negro league past: in May 2011, the city of Homestead rehabilitated previously mentioned Homestead Grays Bridge and, as part of the process, erected eighteen signs on the structure in honor of the memory of the Grays and Crawfords.

2015

In spring of this year, Sean Gibson visited PNC Park for some meetings related to the Josh Gibson Foundation–a Pittsburgh-based non-profit with a mission of youth outreach through educational and athletic programs. Even though Legacy Park was not part of the meeting agenda, Gibson was told of the organization’s plans to renovate PNC Park–which included stripping Legacy Square of its statues. The explanation given by the Pirates was that Legacy Square and the popular left field concourse now attracted “too many” fans, so it would be prudent to spread fans more evenly throughout the ballpark. This was an identical problem faced by the Washington Nationals this offseason is well, but the Nationals chose to simply relocate their statues to another part of the stadium before the season began. The Pirates were not sure of what to do with their own statues, so they asked Gibson. He suggested spreading the seven statues throughout the ballpark, perhaps even naming sections of the stadium after each ballplayer to create better wayfinding and to better incorporate the city’s Negro leagues past into PNC Park. The Pirates response was “We’ll think about it.”

Not long after leaving PNC Park, Gibson discovered the Pirates outright discarded the large bats decorating Legacy Square; he then quickly contacted the Pirates and said he would take all seven statues. The Pirates agreed to donate the statues to the Foundation, but demanded they be removed as soon as possible. The Josh Gibson Foundation effectively had just a few days to coordinate the movement of seven full-scale bronze statues with no storage space or transportation resources at hand. After exploring a few options, Gibson contacted friends at Pennsylvania-based Hunt Auctions to, at the very least, arrange transporting and storing the statues. Ultimately, the Josh Gibson Foundation decided to allow the auction of the statues: the Foundation had no display space, no storage space, and no other cultural organization in the area was willing to take on the statues. The Pirates made a business decision and, in doing so, forced a question with no clear answer upon the Josh Gibson Foundation. The seven statues thus went up for auction during MLB All-Star Weekend FanFest, and each went for more than five times the expected return for a grand total of $226,950 (with the Josh Gibson Foundation receiving about 75% of the proceeds after Hunt Auctions took their cut). Although the Foundation’s return on the statues was quite significant, Sean Gibson himself was none too happy with the outcome, succinctly stating: “No dollar amount is more important than our history.”

Further confounding the Pirates’ relationship to the Negro leagues comes from the club’s interleague series with Kansas City, one week after the statues went to auction, the Pirates traveled to Kansas City for an interleague series. During this series and with no sense of irony, ROOT Sports–the local broadcaster of Pirates games–promoted the Pirates players’ visit to the Negro Leagues Museum in Kansas City. ROOT reported that players found the experience to be enlightening and even humbling. A few players spoke of the “debt” they owed Negro leaguers. No mention was made by ROOT of Legacy Square.

In place of the statues in Legacy Square, the Pirates installed banners along the walls. One side commemorates Negro league players, the other current Pirates players. The Pirates argue the Legacy Square banners are a less intrusive, yet equally effective in memorializing Pittsburgh’s pre-integration African-American star ballplayers. To editorialize a bit, I personally disagree. I was at PNC Park this past August and searched for Legacy Square. I couldn’t find it, so I asked an usher for directions. Turns out, we were standing in Legacy Square, almost exactly on the spot where the Satchel Paige statue stood six months earlier. At the time of the SABR Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference during the first weekend of August, the banners weren’t even on display; quoting conference attendee and art historian Lizz Wilkinson: “The inability of the Pirates to correctly construct the banners initially or to replace them in a timely fashion further exemplifies how the Pirates are disregarding the legacy of this history.” Assuming re-installation for next year, the banners are fine as a form of passive commemoration, but they are absolutely no substitution for the active interpretation of the original Legacy Square space.

Concluding Thoughts

From a historian’s perspective, it seems most likely the Pittsburgh Pirates, emboldened by their recent success and new ownership, simply decided as an organization that they don’t need Pittsburgh’s black history anymore. The Pirates are effectively saying that the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays have nothing to do with the Pirates anymore, and if you want the Crawfords or Grays–or black history in general–then go to the Forbes Field landmark, the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum, or the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. While the Pirates distance themselves from Pittsburgh’s black history, other teams continue to emphasize their city’s black history in permanent ways. Notably, the Cleveland Indians constructed a statue of Larry Doby during the same month of the Legacy Square auction, the Los Angeles Dodgers announced plans for a new Jackie Robinson statue, and the Kansas City Royals continue to develop strong partnerships with the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

To be entirely clear: there was absolutely no reason for the Pirates to remove these statues. The Pirates, as clearly stated in 1988, historically played a significant role in keeping African-American ballplayers out of the major leagues for over half a century. If the Pirates want to market the club’s past, then they must acknowledge the Pirates pre-integration past and their Pittsburgh peers in the Grays and Crawfords. The decision to keep or remove these monuments was, of course, ultimately the Pirates and the Pirates alone (since they own PNC Park), but the club acted in an authoritarian manner with absolutely no input from the local community or even the Pirates fanbase. If rumors are true that the Pirates are establishing a hall of fame in the near future, then this Legacy Square debacle speaks poorly of the organization’s current abilities of managing public sport history.

Rather than speak on this further, I finish with another quote from Sean Gibson, this time from October 15, the day after the Pirates’ recent playoff defeat: “To me, that money will be gone in a few years. My history is priceless. Yesterday, the Pittsburgh Pirates had one of the highest attendances of the year, and how many people saw these statues? And it’s not just my history, but part of the city, club, regional, and national history. I’m not mad, just disappointed.”

Author’s Note: I would like to thank Rob Ruck, Sean Gibson, and Lizz Wilkinson for taking the time to speak with me about this story. The Pittsburgh Pirates organization declined comment.

Josh Howard is a PhD Candidate in the Public History Program at Middle Tennessee State University. His research interests include sports history, Appalachia, and public history. His ongoing dissertation research explores the use of informal data collection techniques in museum visitor studies. Most recently, he completed a web exhibit and archive based on the Wendell Smith Papers for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. He is also the social media editor for this blog. Get in touch with Josh at Joshua.Howard@mtsu.edu or on Twitter via @jhowardhistory.

Pingback: Statues & Pictures: Thinking Through Commemoration at PNC | Andrew McGregor

Personally i believe that the Pittsburgh Pirates should be ashamed to get rid of such history. The statues of players they took down had to go through discrimination. The pirate did the right thing honoring the players for the Grays and Crawfords. They honored hall of fame legends like Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Satchel Page and Smokey Joe Williams. They took something sacred for these ball players, and their families. The Pirates tried to erase these men for their history. Even when Pittsburgh was one of “defacto” teams that tried to eliminate the separation of sports and race. The Pirates should be ashamed of what they did. I think they need to realize that these statues are apart of Baseball history.They should have never been taken down.

LikeLike

The Pirates displayed childish acts by removing the statues of the Negro league players at their ballpark. They traded in a modest tribute for a cheesy rememberance. After the statues were taken down the Pirates must’ve realized they made a poor decision so they hung up the banners of the Negro league players the cover their mistake. I thank the author of this article, Josh Howard, for touching on this subject. I ask why the Pirates organization was never harshally question about this situation. I feel if this was released to the media earlier then this would’ve never happened. The media should’ve exposed this terrible matter more and caused the Pirates organization to second guess themselves. I also believe the Pirates should apologize to the families of these players.

LikeLike

The main focus of this writing is racism with baseball through out time. The team that is focused is pirates and how race affected their team. There was a group of black males who joined the team to make a change and that they did. More black men started to play the sport and people started to accept it. There was still adversity to over come but they prevailed. They did so well that later on in the years to come the team built statues of the men in their hall of fame. The Pirates are still not a great team today but the statues still stand.

LikeLike

I think that it was the wrong decision to remove these statutes and bats, which were honoring Negro League baseball players. These players were all role models for young African American baseball players, they showed them that if they tried hard enough it was possible to achieve there goals of making it to the Major Leagues. Especially seeing how the Pirates were one of the first teams to truly honor these Negro League players because no other teams were doing this at the time. What do you think the Pirates should have done with the statues? Should they just have spread them out like Gibson said?

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Alex. I totally agree with you that the Pirates should not have removed the statues. Ultimately, my thoughts are that the Pirates should have asked for advice from other groups, specifically Pirates fans, Pittsburgh residents, local historians, and those connected to the Negro leagues (such as living players like Monte Irvin and family members like Sean Gibson). I am confident that a compromise could have been reached where the statues were either (1) redistributed throughout the stadium, or (2) gifted to a Pittsburgh-based institution willing to exhibit them. I’m a bigger fan of choice number one personally.

Of course, in both of those scenarios, the Josh Gibson Foundation doesn’t get money, but Sean Gibson himself said that he would rather keep his history rather than take the cash.

LikeLike

Josh Howard the author of Disappointment in Pittsburg: How the Pirates Ditched Pittsburgh’s Negro Leagues Past makes many good points as to how the Pittsburg Pirates mess up Legacy Square and along with messing it up they’re also throwing away Negro pastime. On another hand though how are they ruining the pastime? What do you think possessed the Pirates to actually put those statues up in the first place? “The Pirates were a bit slow to field a black ballplayer (1954, seven years after Jackie Robinson)” Josh Howard actually says this as he goes on adding how the Pirates were a very racist team at the time and it makes me think did the Pirates put up those statues to make a statement to the MLB? Did they put them up in another way of saying sorry for being racist all those years, here are statues of seven of our finest Negro players to prove we no longer are? I’m not saying that the Pirates should’ve gotten rid of the statues, I myself actually believe they should’ve kept them but they didn’t and that’s their chose to do so or not. The only good thing about all of this is that they’re not forgetting those players they just simply changed statues to banners for their own good. “The explanation given by the Pirates was that Legacy Square and the popular left field concourse now attracted “too many” fans, so it would be prudent to spread fans more evenly throughout the ballpark”

LikeLike

I strongly believe that it was a poor decision to take down these statutes and bats which represented Negro League baseball players. The Statues were in place for players whom may represent role models to young upcoming players. It was an example of lessons learned and that could be taught in any era. With hard work its possible to achieve any goal. Hanging up the banners in place of the statue to honor those Negro League baseball players was a great call by the Pirates though, I believe they knew they could not just erase their history and had to in place replace what they had knocked down.

LikeLike

History is important and the history of baseball seems to be an intricate part of the American history. I think it was very improbable and an insult to baseball fans of Pittsburgh in order to adjust the way fans were led into the stadium. Besides that point, what do you think is a motive for the new manager of the stadium to do such a thing? I agree with you that the idea of spreading the statues out and naming sections within the stadium would have an equal amount of changing the layout plan, but allowing fans to keep in time with history and find things out that they previously did not know about the segregation of black players within baseball and how equality was brought about.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this story. I had the honor of seeing these statues in Legacy Park shortly after they were originally erected. Perhaps no city in America has a richer Negro League history than Pittsburgh. The Pirates action is thoughtless and disrespectful at best. Ultimately, it is shameful. But being so, isn’t it largely in line with the rest of baseball’s racial history?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Q&A with Neftalie Williams, Research Director of The African American Experience in Major League Baseball Project | Sport in American History

Pingback: Towards a Public Sport History | Sport in American History

Pingback: Towards a Public Sport History « Sport Heritage Review

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History

Pingback: PNC Park – Curve in the Dirt.com

Pingback: MLB Is Considering Adding the Negro Leagues to Its Official History – Hot & Latest News