By Cat Ariail

At the 1959 Pan-American Games in Chicago, Illinois, Carlota Gooden, a twenty-two year-old Panamanian sprinter descended from Barbadian canal workers, won two silver medals and a bronze. Her performances in the 100-meter sprint, 4×100-meter relay, and 60-meter dash entered her name in the official records of international track, a permanent inscription that asserted her status as an athletic representative of the nation of Panama. However, in 1940, U.S. census takers in the Panama Canal Zone labeled three year-old “Charlotte Gooden” an “alien.” The following year, the Panamanian constitution revoked the citizenship of Jamaican and Barbadian canal workers and their descendants. The fact that Gooden competed in an internationally sanctioned sporting event in the U.S. and won a trio of medals for Panama at the “Olympics at the Western Hemisphere” after being deemed an “alien” and ineligible for citizenship by these neoimperial and state authorities suggests a relationship between sport success and the rights and opportunities of citizenship.

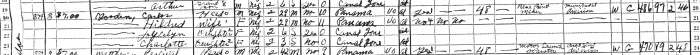

The 1940 U.S. Census entry for the Gooden family – Carlos (29), Hildred (29), Jocelyn (6), and Charlotte (3) – of Barbados Street in Balboa, La Boca, Canal Zone (Image courtesy of ancestry.com).

Within the standardized rules and regulated spaces of sport, athletes from marginalized populations have used their record-breaking, quantifiable achievements to gain access to and recognition in national and international institutions. For instance, former Olympians Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, African American male track stars in the 1930s, occupied crucial positions on Chicago’s Pan-American Games Organizing Committee, with Metcalfe, a city alderman, appointed by Mayor Richard Daley to tour fifteen nations in the Caribbean and Central America to encourage their participation in the Games. Yet, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) stringently has policed which populations of athletes potentially can expand their opportunities through sport. The IOC, dominated by United States Olympic Committee (USOC) in the aftermath of World War II, frequently has reinterpreted existing standards or established new requirements to exclude the athletes of nations deemed oppositional or threatening to the political and ideological priorities of the IOC and USOC. These redefinitions often imposed burdens on female athletes, athletes of color, and athletes from non-western and/or non-democratic nations.

Female athletes of color from the Americas have confronted the most oppressive triad of limitations. Burdened by gender, race, and nation, they nevertheless persistently have navigated within these boundaries to pursue opportunities and attain achievements in sport. Carlota Gooden’s athletic quests in local, national, and hemispheric spaces reveal the powerful prospect of competing between the gendered, raced, and nationalistic boundaries of sport and society. Gooden’s sporting experiences thus suggest the viability of athletic citizenship. An athlete’s individual quest to test and display her athletic ability required continually seeking opportunities, rights, and recognition in sport that, in turn, potentially could secure a greater measure of citizenship.

*************

In 1951, Carlota Gooden received an honor unprecedented for a young West Indian-descended girl living in the Canal Zone when Panama’s Department of Physical Education named the fifteen-year old the nation’s “Athlete of the Year.” Her performance at the 1951 Bolivarian Games in Caracas, Venezuela earned her this recognition, as she won gold medals and set a new Games record in all three events she entered – winning the 50-meter sprint in 6.5 seconds, triumphing in the 100-meter sprint in 12.5 seconds, and anchoring the 49.5-second victory for the 4×100-meter relay team. The Bolivarian Games only offered seven events for women, a fact that reveals the limited competitive opportunities for female athletes as well as the impressiveness of Gooden’s performance. In 1952, Gooden would repeat as Panama’s “Athlete of the Year,” with this subsequent honor further validating her status as a valued athletic representative of Panama.

Crucially, Gooden’s talent allowed her to experience mobility unparalleled for a West Indian Panamanian young woman. She traveled across Panama and the Americas to compete in regional sporting events that, in turn, expanded her athletic expertise and expectations. By meeting and watching great athletes from across the region, Gooden acquired a combination of visual, verbal, and physical knowledge likely inspired improvements in her sprinting techniques and strategies, a refinement of skill that would contribute to her future track achievements. Conversations with athletes from other nations also may have exposed her to new cultural, social, and political ideas. The 1951 Games thus provided Gooden with the opportunity to discover alternative citizenship possibilities, endowing her with new knowledge she could not have acquired without her athletic talent.

The photo Caracas’s $12 million Estadio Olímpico, filled to capacity during the opening ceremonies of the 1951 Bolivarian Games, from the December 9, 1951 issue of The New York Times (Image courtesy of The New York Times).

Along with Gooden, West Indian Panamanians track athletes Adelina Bernard, Jean Price, Clayton Clark, Sam La Beach, and Frank Prince won medals for Panama at the 1951 Bolivarian Games. The track team also included indigenous Panamanian Faustino Lopez, who won gold in the 5,000 meters. This multiethnic cohort of Panamanian athletes particularly dominated the first day of the event, with Gooden, Lopez, La Beach, and a trio of 200-meter sprinters all qualifying for or winning finals. These victorious Panamanian athletes physically asserted themselves as representatives of their nation. For a nation defined by the Panama Canal, and its attendant association with U.S. neoimperialism, this vision was powerful – symbolizing Panama through persons who embodied an ethos of self-determination. The reality within Panama, however, did not correspond with this idealistic image, as divisions of color, language, and culture still impeded the acceptance of West Indians by Latin Panamanians. Nevertheless, the prospect of sport successes trumped nationalistic sentiments, as Carlota Gooden and her fellow West Indian track stars represented Panama at the 1954 Central American and Caribbean Games in Mexico City. Gooden again proved golden in Mexico City, winning gold medals in the 100-meter sprint and 4×100-meter relay. West Indian Panamanians Gloria Tait, Ana Campos, Martin Francis, Frank Prince, and Eric Waldron also secured medal victories. Combined with their achievements at the Bolivarian Games, West Indian-descended track stars’ continued triumphs seemingly affirmed their status as athletic citizens of Panama and the Americas.

However, Carlota Gooden and her teammates found their citizenship under threat soon after returning from the Central American and Caribbean Games. Since the early 1950s, a web of political, economic, and social aims had motivated the U.S. and Panama to engage in negotiations for a treaty that would grant the Panamanian state greater authority. While not the primary intent of the agreement, the eventual 1955 Eisenhower-Remón Treaty resulted in the renegotiation of the status of West Indian Panamanians who experienced the treaty as depopulation and school conversion. Depopulation, the removal of West Indians from the U.S.-controlled Canal Zone, harshly exposed the U.S.’s estimation of the population they imported to build and then sustain their neoimperial space.[i] School conversion, in contrast, reorganized the relationship between West Indians and the Panamanian state. The transition from Zone Colored Schools, administered by the U.S. neoempire, to “Latin American” schools “called for a strictly Panamanian curriculum in Spanish in all West Indian classrooms,” thereby requiring West Indian students “to learn a new language, history, and literature.”[ii] The 1955 treaty thus raised questions about the composition of citizenship, as well as the obligations and opportunities due citizens, in both Panama and the U.S. neoempire of the Americas. This questioning extended to athletic citizenship.

Even though West Indian-descended track athletes successfully represented Panama at the 1954 Central American and Caribbean Games, these athletes did not return to Mexico City for the 1955 Pan-American Games. Evidence suggests that only Latin Panamanian weightlifters competed at the Games. The ethnic composition of the Panamanian team highlights the importance invested in sport as a legitimate symbol of a nation. For individual athletes, competing under the flag of a particular nation presumably certified their national belonging. In 1955, Carlota Gooden and other West Indian Panamanian athletes lost the athletic citizenship they previously had secured. These talented athletes also did not represent Panama at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne. Nevertheless, Gooden persisted. She took advantage of a new opportunity provided by her athletic ability in order to continue to prove her value as an athletic citizen of Panama, the American hemisphere, and the world. In 1955, she earned an athletic scholarship to Tuskegee University, one of the premier African American women’s track programs.

A photo of Carlota Gooden in her Tuskegee uniform (Image courtesy of the Atlanta Daily World, February 6, 1960).

Along with entering a strong black educational institution, Gooden joined a track team and wider culture of black women’s track that provided her with an established structure for continuing to expand athletic opportunities and rights. However, she confronted different boundaries of sport, gender, race, and nation as a student and competitor for Tuskegee, a black woman in the U.S. South and in U.S. sport, and as a West Indian Panamanian female athlete in African American women’s track. In the U.S., as in the Canal Zone and across the Americas, Gooden’s hybridity posed a confluence of potential boundaries that simultaneously erected obstacles and offered openings for seeking athletic citizenship. The 1959 Pan-American Games in Chicago epitomize the multifarious, inconsistent intersection of national, racial, and gender ideologies that mediated her opportunities and accomplishments in sport.

The biggest stage Gooden had participated on thus far, the 1959 Pan-American Games assumed even greater symbolic significance due to its location and timing, occurring in the U.S. a year before the 1960 Olympic Games. For athletes of color and female athletes from across the Americas, the Games served as an opportunity to challenge the boundaries of race, gender, and nation that unduly had limited their sporting opportunities. A record number of nations and athletes participated in the 1959 event, with this large number of non-U.S. athletes of color presaging the possibility of using sport success to display the capacities of all persons of the Americas. Carlota Gooden and her fellow West Indian Panamanian athletes again represented Panama, a circumstance that reveals the flexible subjectivity with which national sporting officials determined those worthy of athletically embodying the nation.

In her qualifying heat for the 60-yard dash, Gooden undauntedly asserted her significant skill, setting a new world record of 7.4 seconds. The anticipated U.S. dominance rendered her record even more powerful. She forced U.S. neoimperial sport, as well as the athletic regimes of all the nations of the Americas, to appreciate her talent. Solider Field, which hosted the track events, customarily had held primarily-white college football all-star games, stock car races, and other special sporting events for mostly white male athletes. The 1959 Pan-American Games represented the first time female athletes of color competed in this arena of athletic privilege. By excelling in this space, Gooden, at least momentarily, challenged common conceptions of dominant athleticism. She demonstrated the great potential of black women and West Indian-descendants to Panama, the U.S., and the wider American hemisphere. Even as her political, social, and cultural citizenships remained contested within her home nation and the broader U.S. neoempire of the Americas, Gooden used sport to claim membership in both these spaces. Eight years of competing in the Zone, across the Americas, and in the U.S. did not guarantee her success, but it endowed Gooden with the ability, knowledge, and confidence needed to set a world record – an emphatic claim to athletic citizenship.

However, Gooden’s moment as the embodiment of global athletic superiority was fleeting. In the 60-yard dash final, Isabelle Daniels, of the U.S. and Tennessee State University, bested Gooden’s world record and won the gold medal. Gooden’s name remained in the record books, though now listed below that of Daniels. And while Gooden did win the silver medal, her second-place victory was anything but uncontested. Trailing Daniels by a mere millisecond, Gooden crossed the finish line at the same moment as the U.S.’s Barbara Jones. The unresolvable Gooden-Jones tie challenged the supposed objectivity of the lines of the track and the seconds on the stopwatch, the unbiased arbiters of track excellence. Gooden’s short-lived world record and shared silver medal thus illuminates the precariousness of relying on sport success to secure a greater degree of national, hemispheric, and world citizenship. Although a millisecond separated Daniels’ gold and Gooden’s and Jones’s silvers, the symbolic value of a singular gold medal far outweighed of that shared silver.

Undeterred, Gooden reinforced her status as a valuable athletic citizen of Panama and the American hemisphere by winning additional medals. In the 100-meter sprint, she won the bronze, falling less than a millisecond short of securing a second silver. She did win an additional silver medal in the 4×100-meter relay, teaming with Marcela Daniel, Jean Holmes, and Silvia Hunte to finish between the U.S. and Canadian squads. Through her multiple medals at the Pan-American Games, in addition to her past achievements, Gooden had accumulated an impressive body of athletic excellence. While her achievements could not guard against all of the racist and nationalist whims of Panama or the U.S., her repeated successes over almost a decade of track competitions had provided her with opportunities, rights, and recognitions that, otherwise, would have been unattainable. In 1960, Gooden would compete in her first Olympics, travelling to Rome to finally represent Panama on the international athletic stage. Although her 12.2-second performance in her 100-meter qualifying heat exceeded her bronze winning 100-meter time in 1959, her effort only led to a fourth place finish, eliminating her from the competition and ending her competitive career.

************

Despite never achieving ultimate international athletic glory – an Olympic medal – Gooden’s career reveals the possibilities of athletic citizenship. The historiography of women’s sport focuses on boundaries crossed, but turning to the spaces between the boundaries tells an alternative narrative of women’s sport, one that privileges actors often invisible or dismissed. Rather than experiencing boundaries of gender, race, and nation as limitations, Gooden discovered and demonstrated their potential for empowerment. While not all female athletes of color from the Americas faced the particular gendered, raced, and nationalistic boundaries that challenged Gooden, the other women who succeeded in the 1950s similarly navigated ever-shifting boundaries to attain measures of athletic citizenship. In conjunction, their individual claims collectively expanded the athletic opportunities, rights, and recognitions available to the wider population of female athletes. Female athletic citizenship pursuits demonstrate that women’s participation in sport has been a series of moments; these moments have not guaranteed a linear, progressive women’s sport movement but nonetheless have established the foundation for the gradual expansion of opportunities, rights, and recognitions for female athletes. The experiences of Gooden are an example of this quest.

Cat Ariail is a PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Miami. She researches women’s sport and race in the late-twentieth century Americas. You can contact her at cat.m.ariail@gmail.com.

Notes:

A note on terminology: Following the example of Kayasha Corinealdi, a scholar of Afro-Panamanian politics and culture, I refer to the U.S. as a neoempire and Panamanians descended from Barbados and Jamaica as West Indian Panamanians (Kaysha Corinealdi, “Envisioning Multiple Citizenships: West Indian Panamanians and Creating Community in the Canal Zone Neocolony,” The Global South 6, no. 2 (2013): 87–88).

[i] Kaysha Corinealdi, “Envisioning Multiple Citizenships: West Indian Panamanians and Creating Community in the Canal Zone Neocolony,” The Global South 6, no. 2 (2013): 94.

[ii] Michael E. Donoghue, Borderland on the Isthmus : Race, Culture, and the Struggle for the Canal Zone (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 119.

Pingback: Review of Testing for Athlete Citizenship | Sport in American History

This is a wonderful story but does not fully reveal how much Carlota overcame in a perfectly segregated community. She was also a good student and one of those young ladies that every young man thought attractive. She comes from a large family with all dedicated to education. She made us all proud so did Gloria Tait who lived on the same building as I and Clayton Clark who lived a few buildings down. Carlota and I went from elementary school to the class of 1955 together–a small, but disciplined group. Thanks for doing this story. Carlota was in the vanguard of great athletes who came out our town. Proud of you TO THIS DAY, Carlota, herrington

LikeLike

Herrington,

Thank you for your comments. If possible, I would love to talk with you further about Carlota, as well as the childhood experiences of you and your peers.

Best,

Cat

LikeLike

Coincidentally, I read this article (which was just sent to me by my nephew) while watching the 2016 Olympic opening ceremonies are occurring. Carlota Golden is my mother and I thank you for this informative and deeply touching article. The article uncovered events that even I was not aware of. I do recall my mother explaining how the U.S. brought “Jim Crow” to Panama, but many of the details were not discussed. Once again, a sincere thanks.

LikeLike

Not Golden… Gooden.

LikeLike

Hi Cecilio,

My name is Nicolle, I work at a TV Station in Panama, and I am making a special about your mother which is airing in the month of october. I would love to interview her and her children. Please contact me so that I may give you further detailes.

ferguson.nicolle@gmail.com

Thank you,

Nicolle

LikeLike

That’s my Mama..

LikeLike

Hi Leroy,

My name is Nicolle, I work at a TV Station in Panama, and I am making a special about your mother which is airing in the month of october. I would love to interview her and her children. Please contact me so that I may give you further detailes.

ferguson.nicolle@gmail.com

Thank you,

Nicolle

LikeLike