By Cat Ariail

At the upcoming summer Olympics in Rio, Jamaica’s Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce will attempt to win her third consecutive gold medal in the 100 meters. Her countryman Usain Bolt also will have the opportunity to accomplish the feat in both the 100 and 200 meters. If they three-peat in the 100, Fraser-Pryce and Bolt will exceed the back-to-back triumphs achieved by Wyomia Tyus in 1968, Carl Lewis in 1988, and Gail Devers in 1996.

Regardless of how Fraser-Pryce’s and Bolt’s bids for Olympic history unfold, the persisting gender disparities in sport coverage make it safe to assume that Bolt’s quests will overshadow the effort of Fraser-Pryce. And even if Bolt three-peats in both the 100 and 200, winning three straight gold medals in the one of the Olympics’ most prominent event should secure Fraser-Pryce a prominent position in the pantheon of women’s track, as well as recognition as an icon of black excellence. Will Fraser-Pryce receive her deserved adulation?

The regard for Wyomia Tyus provides an instructive context for thinking about how Fraser-Pryce might be appreciated. Like Tyus in 1968, Fraser-Pryce is competing in a moment when blackness is being defined. Tyus was not considered a representative of blackness and, in turn, her achievement was not celebrated. Will the same be true for Fraser-Pryce?

The Gendered Black Athlete

Since the rise of Jack Johnson in the early twentieth century, if not before, sport has served as a critical arena for displaying positive visions of blackness globally. With their medal stand protest at the 1968 Olympic Games, Tommie Smith and John Carlos defined the modern black athlete. In Not the Triumph but the Struggle, Amy Bass explores the making of and meanings attributed to Smith, Carlos, and the wider Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) that they represented. Focusing on Smith, Carlos, and OPHR, she critically considers the manifestations and implications of the “organic political discourse [that] actively positioned the [black] athlete in wide-ranging civil rights efforts that accompanied the close of World War II, creating the important social and cultural transformation of a ’Negro’ athlete into a decidedly ‘black’ one.”[1]

Through his 2008 and 2012 Olympic triumphs and subsequent performances, Usain Bolt has communicated modern blackness to the sporting public. Caribbean studies scholar Deborah Thomas defines modern blackness as “a subaltern aesthetic,” where individuals take advantage of the opportunities of the modern capitalist economy to challenge “the maintenance of a particular color, class, gender, and culture nexus that reproduces colonial relations of power.” While Thomas theorizes modern blackness in context of the history of Jamaica’s nationalisms, modern blackness can apply beyond the island. Thomas’s assertion that “the discourse of individualism is infused with a notion of racial progress designed to challenge stereotypical assumptions about racial possibilities” proves relevant for thinking about contemporary athletes of color.[2] With his independent training program, Puma sponsorship, and uninhibited, self-directed stylings, Bolt is an avatar of modern blackness.

Of course, Smith, Carlos, and Bolt, like Johnson before them, all expressed unapologetically masculine blackness. Considering why Tyus could not and whether Fraser-Pryce can represent blackness provides an opportunity to explore the complex relationship between blackness and gender in sport. Do assumptions about blackness, masculinity, and sport prohibit black female athletes from serving as global icons of black athleticism? Or, does our historical moment present possibilities for alternative models of blackness that provide a space for celebrating Fraser-Pryce?

Why not Wyomia?

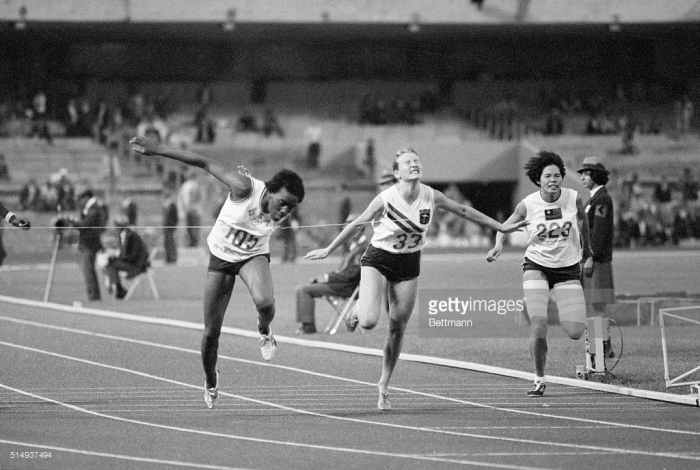

At the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, Wyomia Tyus became the first athlete, of any race, gender, or nationality, to defend her 100-meter gold medal. After Wilma Rudolph received worldwide adulation for becoming the first American and first black female athlete to win three gold medals in a single Olympics in 1960, the sporting public seemingly should have been receptive to another black female athlete who could achieve something unprecedented. Before the 1968 Games, several sports writers in the African American press suggested that Tyus could replicate Rudolph’s triple-gold triumph, as she would compete in the 100 meters, 200 meters, and 4×100 meter relay just as Rudolph did in 1960.[3]

But none recognized that Tyus had the opportunity to complete a previously unattained feat by repeating in the 100 meters. When she won her 100 gold in Mexico City, the Philadelphia Tribune announced “Wyomia Tyus Becomes 1st Woman to Repeat in Olympic 100 Meter,” specifically denoting her gender even though no male athlete had accomplished this feat.[4] The New York Times only mentioned her historic medal defense in the middle of a lengthy article that recapped the performances of American athletes in multiple Olympic events.[5]

Wyomia Tyus captures her second consecutive 100-meter gold medal at the 1968 Olympic Games. (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

The muted reaction to Tyus’s triumph, especially in the black press, proves curious due to Rudolph’s popularity, as well as the circumstances surrounding the 1968 Olympic Games. As demonstrated by scholars, the positions and proclamations of the OPHR dominated the lead up to the Games.[6] Led by San Jose State track coach and sociology professor Harry Edwards, the OPHR proposed that athletes of color boycott the 1968 Olympic Games unless the group’s demands were met. Among other debates, OPHR’s proposed boycott exposed fractures within the black sporting community, as many former black Olympians and prominent black sportswriters opposed the boycott (Louis Moore’s Thursday post describes Jesse Owen’s opposition).

For those who disagreed with the aggressive stance advanced by OPHR, Tyus’s story seemingly could have served as a productive counter. Sportswriters and former athletes insisted participation in the Olympics provided an invaluable platform for athletes of color to demonstrate the capacity of all persons from these populations. The opportunity Tyus had to become the first athlete to win back-to-back 100 meter golds embodied this belief. Tyus’s potential achievement could have served a unifying symbolic role, communicating that black athletes should compete in the Games in order to display how athletes of color push the boundaries of athletic possibility.

Yet, Tyus’s potential for history was not recognized. As noted above, black sportswriters understood Tyus and constructed expectations for her based on the Rudolph framework. This interpretation suggests that, while Rudolph had established a place for black female athletic icons, it was a limited space. Black male sport writers seemingly could not imagine that Tyus could achieve something different from, and possibly greater than, Rudolph. And they certainly could not envision her as a representative of black athleticism. Rudolph ostensibly had proven that black female athletes could serve as racial representative, yet changing historical circumstances had rendered that place questionable.

The prominence of the Cold War in 1960 permitted Rudolph to emerge as an icon of black Americanness, with her success symbolically representing the progression of civil rights in the United States. Both Rita Liberti and Maureen Smith’s (Re)presenting Wilma Rudolph (reviewed for the blog by Cathryn Lucas) and Melinda Schwenk-Borrell’s “‘Negro Stars’ and the USIA’s Portrait of Democracy” discuss the ways in which the United States press and government portrayed Rudolph and her story as illustrative of American values. Racial relations in the United States, however, continued to belie the image of racial equality represented by Rudolph.

Over the course of the 1960s, black athletes played an instrumental role in exposing this lie. Rather than using sport to advocate for racial assimilation, sport became a venue to express racial autonomy. African American athletes involved in the OPHR and other sport-based racial activism used sport to define blackness rather than claim Americanness. Sport thus mirrored the trajectory of the broader civil rights movement. As Bass discusses, these efforts relied on an inherently and unquestionably masculine definition of blackness.

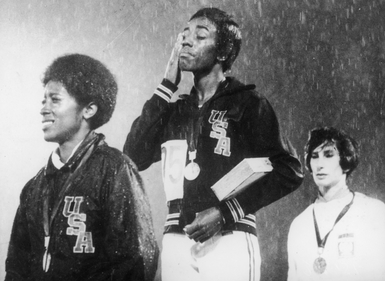

Wyomia Tyus’s emotional medal stand moment at the 1968 Olympic Games. (Image courtesy of Getty Images)

Black female athletes thereby occupied a contested place in the OPHR, which both Bass and Jennifer Lansbury, in her chapter on Tyus in A Spectacular Leap (reviewed for the blog by Lindsay Parks Pieper), chart. These scholars share the multiple narratives that emerged in the historical moment and in historical memory about the involvement, or lack thereof, of black female athletes in the OPHR, with the various individuals involved seeming to advance different stories at different times. Regardless of the historical reality, these conflicting narratives capture the unstable blackness of black female athletes in the late 1960s.

In her analysis of Tyus, Lansbury also emphasizes the importance of femininity to the image of black female athletes. Since assuming head coaching duties at Tennessee State University in the early 1950s, Ed Temple had insisted on the femininity of his athletes, requiring that they be “foxes not oxes.” With her popularity, Rudolph codified this image. In the late 1960s, however, gender expectations were in flux due to the emergence of second wave feminism. As Lansbury captures, Tyus thereby had to navigate carefully the changing demands of race and gender. She forged a middle-road activist role, supporting the cause for black freedom through less heralded actions.

Rather than engaging in a public protest action, Tyus and her 4×100-meter relay teammates’ quietly dedicated their gold medals to Smith and Carlos, who had been expelled from the Games for their medal stand action. Tyus’s response to a question posed by a Cuban journalist about how she experienced freedom as a black woman in the United States further displays her activist adroitness. According to Lansbury, Tyus told Cuban journalists in 1968, “Deep down I believe I enjoy freedom to a certain extent.”[7] After her athletic career, Tyus continued to participate in subtle but significant racial activism. For many years she worked as naturalist in the Los Angeles Unified School District, providing inner-city African American children the otherwise unavailable opportunity to explore the outdoors.[8] However, since she emerged in a moment that privileged public, bombastic, and authoritative racial activism, her more quotidian actions have not received appreciation.

What about Shelly-Ann?

In contrast, the present black activist moment includes and celebrates a greater spectrum of black identity. The Black Lives Matter movement privileges this multiplicity. This broader acceptance of a greater diversity of images of blackness has coincided with a similarly increased appreciation of Serena Williams, both as an athlete and representative for blackness. The Atlantic’s Vann Newkirk III expresses the symbolic power of Williams’s recent Wimbledon title. Placing Williams’s victory in context with the publicized police killings of black men in Baton Rouge and Minnesota, he writes, “Saturday was a rare instance in which a sporting event was transfigured into something more, a symbolic victory that both helped assuage trauma and provided real hope. No living athlete – perhaps of any gender or in any sport – has represented the spirit of hope more than Serena.”[9]

Newkirk III’s sentiments suggest that a black female athlete can serve as a racial representative. Yet, it proves important to recognize that Williams competes in a sport with traditionally feminine connotations, as well as a sport where a black woman, Althea Gibson, pioneered African Americans’ place in the sport. Can a black woman who competes in a more traditionally masculine sport, particularly one that has served a crucible for expressing masculine blackness, gain acceptance as a representative of blackness?

If she wins a third consecutive gold medal in the 100-meter sprint, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce can test this possibility. Thomas’s modern blackness provides a discourse for thinking about this prospect. She asserts “modern blackness is neither intrinsically divisive nor exclusionary. What modern blackness chiefly challenges is the subordination of black people.” “Modern blackness, then, is a call for the fulfillment of a promise that has remained unrealized,” Thomas further proclaims.[10]

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce celebrates at the 2013 IAAF World Championships in Moscow. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia.org)

As a black female athlete competing in a traditionally masculine sport, Fraser-Pryce seems best able to embody “the fulfillment of a promise that has remained unrealized.”[11] A black female sprinter is an ultimate disruptor of hierarchies, problematizing normative ideologies of race, gender, and sport. Fraser-Pryce also challenges traditional arrangements within the world of international sport, since she comes from the small island nation that has displaced the United States’ sprinting supremacy. Furthermore, Fraser-Pryce’s Jamaican identity encourages visions of blackness that can de-center the United States as the locus of black sport identities.

A brief consideration of Fraser-Pryce’s actions on and off the track illuminate that she is a powerful symbol of modern blackness. On the track, she has worn long, flowing hair extensions that often feature bright red streaks, a style that unabashedly reflects the aesthetic identity of black Jamaican women. At the 2013 World Championships in Moscow she even had her extensions specially shipped from Jamaica, telling journalists, “It makes me pretty – prettier.”[12] Fraser-Pryce further has embraced this image, opening a hair care accessories store in Kingston named Chic.

While her actions may appear frivolously or conventionally feminine, Fraser-Pryce’s femininity, grounded in the priorities of Jamaican women, in fact communicates an independent, even radical, feminine identity. Fraser-Pryce’s background gives her consumption-based feminine identity its political power. The product of the impoverished Waterhouse district of Kingston and daughter of a single mother, she told Athletics Weekly in an interview this year, “I suffered from esteem issues because I didn’t have the nice clothes and the nice house and had to take the bus. I wanted to fit in and would make up stories just to be accepted.”[13]

Through her desire to “be pretty” she rejects traditional uplift ideology that encourages assimilation. Rather than “fitting in” she instead has “made up” her own identity in a way that honors from where she has come. When racing down the track, Fraser-Pryce is an advertisement for self-determined black female desires, an embodied announcement of the preferences and pleasures of an often overlooked or taken for granted population. Fraser-Pryce’s self-stylings thus epitomize modern blackness, using consumption to contest traditional racialized gender expectations. Furthermore, Fraser-Pryce has expressed unabashed self-confidence. Aware of the recognition disparity between her and her countryman, she has proclaimed, “I am Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce. I compare myself to nobody. What Usain has, he has. What I have is hard work.”[14]

Yet, she has combined this self-presentation with more conformist activist efforts, establishing a foundation to help underprivileged youth in Kingston. In 2013, Fraser-Pryce founded the Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Pocket Rocket Foundation, which “foucs[es] on the development of promising young athletes in secondary schools by providing them with scholarships to cover their academic costs.”[15] She also has expressed her intention “to build a community centre in Waterhouse; to get Jamaicans to toss away guns and ensure the island becomes a woman’s as well as a man’s world; to become a child psychologist to help develop ‘more people in the world with better values and better morals.’”[16] These initiatives adhere to more conventional modes of uplift, all while challenging prevailing gender arrangements by positioning the protection and priorities of women and children as those of the Jamaican nation.

A 2015 photo of Fraser-Pryce. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia.org)

Fraser-Pryce also has challenged the hierarchies of national and international sport, aggressively advocating for Jamaican track officials to defend Jamaican athletes against accusations of doping. Such accusations render the achievements of Fraser-Pryce and her fellow Jamaicans suspicious, implying that these athletes could only achieve great athletic heights with the aid of performance enhancing substances. Fraser-Pryce has used her status to rectify such perceptions. In 2013, she argued for the unionization of Jamaican athletes. At a 2013 press conference, she captured the need for a union, describing it as, “Somewhere where athletes can have a voice, can have refuge, where we can make a stand for change.” To convey her insistence, she even considered refusing to run, asserting, “If there are certain things that are not up to standard, then that’s the thing we have to do because if we don’t run, they will start to do things.”[17]

By calling out officials, Fraser-Pryce questions the priorities of national and international sport, exposing how they privilege capitalistic arrangements over the autonomy of athletes. She proclaimed, “They are just sitting back enjoying the benefits and the fruits of our labor, but when it’s time to actually do their jobs, they are not doing it.”[18] Her willingness to question these institutions models a form of activism relevant to persons of color who continue to experience the inequities of capitalism in their daily lives. Although the movement for unionization of track and field athletes that emerged in Jamaica and across international track in 2012 and 2013 has faded, the 2016 Olympics could present a prominent platform to revitalize these efforts, with Fraser-Pryce possibly possessing a powerful position through which she can agitate for meaningful change.

Nonetheless, Fraser-Pryce embodies the complexity of modern blackness. She has engaged in a diversity of efforts that blur traditional gender, racial, national, and activist expectations in multiple ways. Possibly, Fraser-Pryce can be described as articulating modern athletic blackness, displaying modern blackness in the sphere of sport in various ways that speak to the flexible, non-static black activisms of 2016. As an exemplar of modern athletic blackness, Fraser-Pryce, if/when she wins a third consecutive 100-meter gold medal, should receive recognition not only for embodying female athletic excellence or black female athletic excellence but black athletic excellence. This recognition could, in turn, celebrate Fraser-Pryce as a representative blackness more broadly, as she has dedicated herself to honoring and sustaining black identity and livelihood in ways relevant both inside and beyond her nation.

In her study of the making of the black athlete, Bass realized that, “While often hailed as an icon of racial progress, the black athlete creates a potentially injurious basis for more comprehensive designs of black identity.”[19] Bass demonstrates that unquestioned masculinity and “unreconstructed sentiments of racial difference” have been the primary consequences of the black athlete image established in the late 1960s.[20] The idea modern athletic blackness provides a contemporary framework that addresses these limitations, instead presenting a model for black iconicity that better accepts and accommodates a black female athlete as a representative blackness.

1968 was not ready for the potential represented by Wyomia Tyus. Is 2016 ready for Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce?

Cat Ariail is a PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Miami. She researches women’s sport and race in the late-twentieth century Americas. You can contact her at cat.m.ariail@gmail.com

Notes

[1] Amy Bass, Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002),82.

[2] Deborah A. Thomas, Modern Blackness: Nationalism, Globalization, and the Politics of Culture in Jamaica (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), xxviii-xxix.

[3] “Coach Says U.S. Gals Can Win Big in Olympic Track,” Chicago Defender, 9 October 1968; “Olympic Win Would Put Wyomia in Special Class,” Baltimore Afro-American, 12 October 1968; “Wyomia Angling for Three Medals,” Baltimore Afro-American, 19 October 1968.

[4] “Wyomia Tyus Becomes 1st Woman to Repeat in Olympic 100 Meter,” Philadelphia Tribune, 19 October 1968.

[5] “Oerter Takes Record 4th Straight Olympic Gold by Winning Discus,” New York Times, 16 October 1968.

[6] Bass; Donald Spivey, “Black Consciousness and Olympic Protest Movement, 1964-1980,” in Sport in America: New Historical Perspectives, Donald Spivey, ed. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985); Douglas Hartmann, Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and their Aftermath (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

[7] Jennifer Lansbury, A Spectacular Leap: Black Women Athletes in Twentieth-Century America (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 2014), 176.

[8] “Wyomia Tyus: A Child of Jim Crow, She Refused to Run Second to Anyone,” People, 15 July 1995, accessed 27 July 2016, http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20141792,00.html.

[9] Vann R. Newark, “Serena Williams is the Greatest,” The Atlantic, 11 July 2016, accessed 22 July 2016, http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/07/serena-williams-wimbledon-race-message/490679/.

[10] Thomas, 242-243.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Fraser-Pryce (100), Oliver (hurdles) strike gold,” Traverse Record-Eagle, 13 August 2013.

[13] Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce quoted in Stuart Weir, “Shelly-Ann Fraser Pryce’s journey to the top,” Athletics Weekly, 23 January 2016, accessed 21 July 2016, http://www.athleticsweekly.com/featured/shelly-ann-fraser-pryce-journey-to-the-top-38221.

[14] “Fraser-Pryce (100), Oliver (hurdles) strike gold.”

[15] Ryan Jones, “Pocket Rocket Foundations off and running,” The Jamaica Gleaner, 15 May 2013.

[16] Ian Chadband, “Shelly-Ann Fraser’s rise from poverty to one of the world’s best sprinters is remarkable,” The Daily Telegraph, 29 October 2009.

[17] Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce quoted in André Lowe, “ ‘You must defend us’: Fraser-Pryce hurt by doping criticism,” The Jamaica Gleaner, 16 November 2013.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Bass, 5.

[20] Ibid., 6.

As usual we can expect nothing but the best from Cat Ariail. This post is important in t hat when track and field athletes receive little to no attention. Women athletes in all sports receive little to no attention. But lets start with the basics: track and field receives little to no attention in the US. To watch a meet you need one of those special cable packages that has these unknown stations in it just to watch. Even in this Olympic year you still don’t see coverage unless it is a doping scandal. Second, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce runs for Jamaica. Third, she did not attend a US college (like a lot of Jamaican sprinters) and, finally, she has a doping mark against her. Taken together all of these mount to why she is not receiving attention. These items are although not entirely but somewhat similar to Ms. Tyus who was running at a time when it was easy to question female athletes and why they were involved in sports in the first place. Thanks for the piece. I learn so much when I read Cat’s work!!

LikeLike

Pingback: 5 Athletics Races & Athletes I’m Eager to Watch in Rio | Andrew McGregor

Pingback: Roundtable Reflections on the Rio Olympics, Part 2 | Sport in American History

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History