Since this is my first post, I’ll introduce myself and how I found my topic. My name is Hunter Hampton, and I am a Ph.D. candidate in history at Mizzou. I am working on a dissertation on muscular Christianity in 20th century America. Unlike some of my colleagues that popped out of the womb with a desire to be an academic and a dissertation topic in hand, I stumbled into the profession and my project. During my master’s program, I took a historiography class. The professor gave all of the students the assignment of finding an untouched subject on which to write our final paper. He told us that it should be a topic that would hold our interest for over a decade. I froze. I had no idea what to write about. After I met with my professor to ease my concerns, he asked me what interests me. I told him I liked sports, the American West, and religion. With a shrug, he wished me happy hunting. After a few weeks of searching online and in the library I finally found my topic in Endicott Peabody (pronounced pee-bidy and said as fast as possible). He captured my attention, and has held it for half a decade.

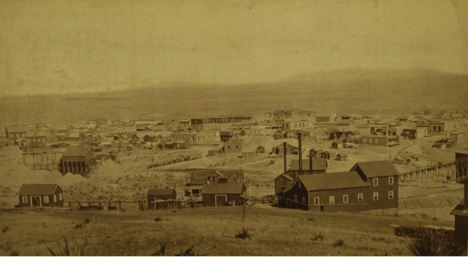

On January 28, 1882, Endicott Peabody stepped out of his carriage onto the cold, dusty streets of Tombstone. As a New England born, British educated, upper-class Cambridge seminary student, Peabody seemed an odd fit in the silver mining boomtown in southern Arizona. During his journey, he had heard various rumors concerning Tombstone. A few months before his arrival,  Tombstone blazed into the pages of Western lore with the Shootout at the O.K. Corral. Well aware of Tombstone’s reputation, Peabody rode into town prepared to fight for the citizens’ hearts and minds. Compared to the other ministers in the town, his ministerial methodology and physique set him apart. Standing over six feet tall, with a muscular build, he struck the citizens of Tombstone as different. His six-month tenure in Tombstone confirmed their suspicions. Instead of spending his time and efforts on recruiting the female members for his congregation, he focused on the men. He began connecting with men on their own terms. He believed an active faith would save the bodies and souls of Tombstone. Not initially carrying a firearm, though that would come, Peabody possessed a new, unique weapon for his ministry, baseball.

Tombstone blazed into the pages of Western lore with the Shootout at the O.K. Corral. Well aware of Tombstone’s reputation, Peabody rode into town prepared to fight for the citizens’ hearts and minds. Compared to the other ministers in the town, his ministerial methodology and physique set him apart. Standing over six feet tall, with a muscular build, he struck the citizens of Tombstone as different. His six-month tenure in Tombstone confirmed their suspicions. Instead of spending his time and efforts on recruiting the female members for his congregation, he focused on the men. He began connecting with men on their own terms. He believed an active faith would save the bodies and souls of Tombstone. Not initially carrying a firearm, though that would come, Peabody possessed a new, unique weapon for his ministry, baseball.

Scholars mark muscular Christianity’s creation during the waning years of the 19th century. Victorian culture was in a state of crisis. Aristocratic children often lay pale and bedridden in their homes suffering from neurasthenia. With a perceived “softness” among men, especially clergy, the solution was rediscovering their masculinity through a strenuous life ethic. These late Victorians believed physical exercise and an active faith embodied the remedy for their malady. A logical arena in which to experience the strenuous life was sport. At this time, baseball engulfed the nation. Examining the relationship between religion, baseball, and muscular Christianity in the American West reveals the innovation of Endicott Peabody to interact with the rugged male dominated society, adapt to the individualistic culture, and meet spiritual needs of their Western congregants.

Born on May 30, 1857, Endicott Peabody came into a wealthy New England family. While at school in England he took an interest in various sports. Peabody’s biographer described him as tall, strong, and graceful. Sometime, in the early months of his seminary education, Peabody received a call to fill in as the minister for the Episcopal Church in Tombstone, Arizona. Grafton Abbott, a friend of Endicott’s older brother Francis, had traveled to Tombstone chasing opportunity in the recently discovered silver mines. The founding rector of the church clashed with the congregation, and left town soon thereafter. Peabody struggled with the decision, but he accepted the appointment to stay in “the rottenest place you ever saw” for six months.

One of Peabody’s primary actions in Tombstone was ministering to the miners and he relied on his sporting ability to interact with a class of men overlooked by pastors before him. His tool was baseball. He frequently traveled to mines outside of town to play baseball with the miners. Of one such game he wrote, “I was glad to thoroughly get to know the men better.” This technique earned the respect of the miners. In a letter back east Peabody told about one miner who said, “Why is that the minister there? Well, I’ll be damned if I don’t think more of him than I did before.” Over the course of his time in Tombstone, Peabody continually met with various men, mostly miners, in hopes of starting a team.

Within a month of Peabody’s arrival, the men of Tombstone were regularly playing baseball. Out on a visit to a female member of his congregation, Peabody passed several men throwing the ball around. Two hours later, Peabody left the field, but felt that he “did not play very well still enjoyed it very much.” He maintained a high standard for his play. For example, after one satisfying day at the field he wrote, “Rather good form- hitting 3 times and one to the fence and made a rather swaggering catch.” The usual end of the game did not come from fatigue, but from the ball being torn to pieces. He habitually shortened his house calls in favor of a baseball game. For Peabody, this was not neglecting his clerical duties, but rather he viewed baseball as evangelism and exercise, both essential for changing Tombstone’s society. While he desired an organized league, the spontaneous baseball excursions made up the majority of his play and pastoral visits.

On April 26, 1882, Peabody took part in the organization of the first Tombstone baseball team. He became the treasurer of the team, something he found boring. He, however, understood his higher purpose for helping establish the team as the pro bono ecclesiae. Typically, the members of the Tombstone team would play games against the various mines that had enough men to field a team. Before long, the team moved him into the position of Vice President. With his new position came added responsibilities. One day, when he was not feeling particularly well, he mounted a horse, and worked on leveling off the field for over two hours. Though overworked and underpaid, Peabody understood the power of baseball for his ministry to the men of Tombstone. The game provided him the opportunity to travel around the Arizona countryside to interact with the miners.

Peabody’s adoption of sports for evangelization purposes represents one of muscular Christianity’s primary innovations. His neighbors in Tombstone took notice of his blend of masculine activities and religion. According to the Tombstone Epitaph the town got “a parson who doesn’t flirt with the girls, who doesn’t drink beer behind the door, and when it comes to baseball, he’s a daisy.” What set Peabody and other muscular Christian ministers apart was their willingness to disregard the Victorian stereotype of effeminate preachers and embrace the cultural desires of American men.

The actions of Peabody left an indelible mark on the American West. Through his endeavors, Peabody successfully established a church founded on muscular Christianity. As Reverend Peabody’s tenure in Tombstone was ending, he sought a replacement minister capable of holding his own on the baseball diamond. This ensured the future minister would “be brought into contact with men whom he might not otherwise meet.” Through these interactions, some of the ministers of Tombstone earned the respect of the miners. He found his man in Isaac Bagnell. Peabody’s primary goal for his successor was to continue the implementation of muscular Christianity as the tool to reach Tombstone’s citizens.

The most obvious example of Peabody’s legacy in Tombstone, can still be found on the corner of Third and Stafford, two blocks from the O.K. Corral. There stands St. Paul’s Episcopal Church of Tombstone. It is on the same site acquired by Peabody almost a century and a half ago. While no trace of a church baseball team is readily available, the church continues to serve the community of Tombstone.

After his experiences in Tombstone, Peabody returned to New England a changed man. He instilled the lessons learned into prominent shapers of American society by founding the Groton School outside of Boston. When Peabody passed away on November 17,1944, he had educated Theodore Roosevelt’s boys, advised Jacob Riis on his urban reform efforts, and served as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s mentor. In Peabody’s obituary for the New York Times, F.D.R. reflected, “As long as I live his [Peabody’s] influence will mean more to me than that of any other [person] next to my father and mother.” The life of Endicott Peabody illustrates the potency of muscular Christianity and the impact the American West had on shaping him and his ministry.

The implementation of muscular Christianity through baseball in the American West by Endicott Peabody leads to several conclusions about the relationship between sport, the West, and religion in 19th and 20th-century America. First, Peabody’s transformative experience in Arizona marks the influence of the American West on muscular Christianity. In Tombstone, Peabody acknowledged that he was an outsider. He was not a cowboy, miner, prospector, gunslinger, or entrepreneur. However, this did not stop him trying to imitate them. To gain the rugged nature that he lacked, Peabody purchased all of the necessary items. He bought a cowboy hat, pistol, chaps, and horse. He believed these purchases and his jaunts in the countryside offered him the authentic experience he hoped to obtain when he traveled west. Despite all of his purchased Western wearwhat ended up winning the respect of the citizens of Tombstone was his love of baseball. Instead of fearing the rise of American sports culture, muscular Christian preachers in the American West embraced the game to reach their communities. As Peabody’s experience shows, the American West did not act solely as a receptor of religion from the East, but served as a proving ground for muscular Christians that in turn reshaped American Christianity and culture.

Second, muscular Christianity from its start embraced controversial sports. While some pastors focused on enforcing blue laws against baseball, muscular Christian ministers used the game to further their cause. As the 20th-century progressed, they maintained this characteristic. Religious universities like Notre Dame and BYU started football programs in the first quarter of the century exemplify this ingenuity. A century later we have fighting pastors as discussed in Adam Park’s post two weeks ago. Muscular Christianity has never been regressive. Rather, it blurred the line between savage and civilized in order to attract new converts, reshape physiques, strengthen faith, and gain moral authority.

This combination of baseball and Wild West culture gave birth to a movement that changed the practices and perceptions of Christianity throughout the 20th century. The strongest days of muscular Christianity were still to come. In the decades to follow, the emphasis on a participatory faith grew into movements like the Social Gospel,Boy Scouts, Christian summer camps, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, Promise Keepers, and Fight Church. Though no muscular Christians find themselves combating Wild West shootouts today, they, like their 19th-century comrades, remain focused on infusing American churches and culture with sports and masculinity. Consider who is the face of evangelical Christianity today. Not a minister, author, or scholar, but an out of work quarterback, Tim Tebow.

Hunter Hampton is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Missouri. He can be reached at hmhyn7@mail.missouri.edu.

Ciao!!!

I loved the post! Do you plan on posting more in the future? I’d like to read more about the relationship between Peabody and FDR. Thanks again.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on DailyHistory.org and commented:

Hunter Hampton at Sport in American History has a post on how ministers not only spread the gospel, but baseball. Most historians are familiar with Theodore Roosevelt’s 1889 speech “The Strenuous Life” where he advocated on behalf of a “life of toil and effort” to not only improve ourselves, but to promote American imperialism. Hampton explores one of the prophets of the strenuous life, Endicott Peabody. Ann Coulter’s recent vitriolic attack on soccer is descendant of muscular Christianity, Roosevelt’s “Strenuous Life” and American exceptionalism.

LikeLike

Pingback: American Studies, American Sport | Sport in American History