By Russ Crawford

Yesterday, two teams from the National Football League (NFL) will played the first of three scheduled games in England this season. Two games take place at Wembley Stadium, the venue for twenty-three previous NFL games played across the pond since 1983,[1] and the third is to be held at Twickenham Stadium. The Jaguars, Colts, Giants, Rams, Redskins, and Bengals are scheduled to take the trip this year, and the league plans to continue playing at least two games in Wembley through 2020. Although the 2015 match between the Jacksonville Jaguars and the Buffalo Bills, which Robert Booth of the Guardian described as being played “to a backdrop of semi-naked cheerleaders, pyrotechnic display and military salutes,” lost around £650,000, the NFL continues to explore the possibility of fielding a team playing out of London. [2]

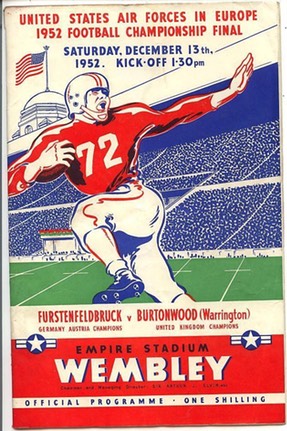

Wembley Stadium’s website indicates that the 1983 match between the Minnesota Vikings and St. Louis Cardinals was not the first American football game to have been played at the stadium. They correctly identify the 1952 USAFE final as being the first game in that location,[3] but the American brand of football has a much longer history in England that stretches back to 1910.

A Fleet of Footballers: The U.S. Navy and International Gridiron Games

During the first decade of the twentieth century, the United States began to take a larger role in the world. The main instrument for showing the American flag internationally was the U.S. Navy. American ships visited all corners of the world, and on many of their stops, they demonstrated the relatively new game of American football. The first games were played by the crews of ships belonging to American president Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet that toured the world from 1907 to 1909. One of the first football games played outside of North America was a 1909 contest between teams from the USS Kansas and the USS Minnesota that in Nice, France.[4]

Image from The Graphic, 1910.

Football, which had been included in military athletic programs since the Spanish-American War in 1898, continued to be a feature of sporting programs for soldiers and sailors.[5] It was the navy that brought football to Great Britain for the first time when two battleships, the USS Idaho and the USS Vermont, played a Thanksgiving Day game on November 23rd, 1910 at the Crystal Palace. The Daily Mirror sponsored the game and provided the Daily Mirror Silver Cup, which was presented to the team from the Idaho by the Duke of Manchester. A crowd of around 10,000 turned out to watch the Idaho players defeat the Vermont team by a score of 19-0. The event was so popular that the newspaper staged two more games. The second contest, played between the Idaho and the USS Connecticut on December 3rd, also took place at the Crystal Palace. Idaho won again, defeating Connecticut 5-0, before a crowd of 12,000 curious spectators. This time the Duchess of Marlborough presented the team with yet another cup. The final match, this time between teams from the USS Georgia and USS Rhode Island, took place at the Stonebridge Sports Ground in Kent, and drew only 4,000 spectators. Georgia defeated Rhode Island 12-0, and presumably won a cup for themselves.[6]

During the three game series, the British newspapers were skeptical of the new game, to say the least. Their reports emphasized the violence that marked football. The Graphic told its readers that “North American football has the reputation of being more dangerous than the South America revolution! – on the very day this game took place a boy was killed in a match at Winsted, Connecticut – but, happily, the Crystal Palace match passed off without a mishap, the Idaho team winning by 19 points to nil.”[7] The Illustrated London News also mentioned the player killed in Connecticut, commenting darkly that “It is further interesting to note, perhaps, that only the other day, an American football player was brought up, after a game in which a player was killed, on a technical charge of murder. He was exonerated and acquitted, but that it should be possible even for such a charge to be make shows how rough-and-tumble a game American football can be.”[8]

Although the series seemed to be popular with the British, at least as a sideshow spectacle, there was no apparent effort to follow-up the games by British athletes. Football therefore disappeared from the British Isles, aside from the occasional newsreel footage of Harvard vs. Yale games, or the rare movie such as Harold Lloyd in The Freshman (1925). However, when American servicemen began to arrive in the British Isles during the build up for the counterattack against the Germans in World War II, the GIs brought football equipment with them.

Wartime Football Abroad: The Tea and Coffee Bowls

Football returned to the UK when the Hales defeated the Yarvards 9-7 in front of 9,000 spectators in Belfast. The teams were given their tongue in the cheek names by team captains Cpl. Robert Hopfer of the Yarvards and S/Sgt. Arnold Carpenter of the Hales. It is likely that the majority of the “puzzled” fans were not cognizant of the inside joke, and the Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper, mentioned that they weren’t even sure of the final score. Puzzling or not, the game raised money for the Royal Victoria Hospital along with the Soldier’s, Sailor’s and Airman’s Families Association. It also signaled that football had returned after a thirty-two year absence.[9]

During the war, there would be a number of games played wherever American servicemen were billeted. Many games were played at the company or regimental level, and were designed to keep the overpaid and over sexed Americans out of trouble, but others were designed to entertain the troops and the local populace. Among these mass spectacles were the Tea and Coffee Bowls.

The idea for the first Tea Bowl originated when Major Dennis Whitaker, a former quarterback for the Hamilton Tigers of the Canadian Football League, and a Special Services lieutenant met in a pub, and began talking football. The result of the chance meeting was the Tea Bowl. The game was to be a hybrid, with the first half played under American rules, and the second under Canadian. The Canadians formed a team called the Mustangs, stocked with former CFL talent, and the Americans, led by PFC Frank Dombrowski, organized the Central Base Section Pirates.[10] Even during the spectacle, won by the Canadians 16-6, the war was hard to forget, and Royal Air Force Spitfires flew cover over the game in case the Luftwaffe decided to attack.[11]

Stung by the loss at the game Americans consider their own, they called for a rematch, and this time stacked a team to match the Canadians professionals. Key to the victory of the Infantry Division Blues, in what was dubbed the Coffee Bowl, was the play of Sgt. Tommy Thompson, who had previously played with the Philadelphia Eagles of the NFL. Behind his efforts, which Stars and Stripes described as being a “one-man-gang performance,” the Blues defeated the Mustangs 18-0 before a crowd of 55,000 at the White City Stadium. The March 20, 1944 game still featured a switch in rules at halftime, but the Mustangs had no answer for Thompson, who threw for two touchdowns, returned punts for a 20 yard average, and ran at will over the Canadians.[12]

With the success of the Tea and Coffee Bowls, the Special Services Branch continued staging mass spectacles to entertain the troops. A few months after D Day, the Eighth Air Force (Army Air Corps) Shuttle-Raders defeated the Navy Sea Lions 20-0 in front of 40,000 at the White City.[13] This game was named the G.I. Bowl and it was followed by Tea Bowl II, this time contended by the Air Service Command Warriors who defeated the Shuttle-Raders 13-0. White City once again was the venue, and 25,000 spectators turned out to view the action.[14] The steady decline of spectators was likely due to the increased tempo of combat as Allied forces neared and then penetrated German territory. Despite that, the various branches of the military still played their games. Leagues in Britain and on the continent played as many games as possible, though one contest between the winner of the Normandy Football League and the Eighth Air Force All-Stars had to be cancelled, presumably because of the need for personnel to concentrate more on bombing runs than off tackles.[15]

Postwar Football: The US Air Force Europe Sports League

After the war, Americans retained a presence in the UK, particularly on Air Force bases. Football continued there, but only of the touch variety. In 1951, the US Air Force Europe (USAFE) Sports League began to sponsor full tackle football at bases in the UK. During most of the Cold War, seven teams contended for the USAFE crown from British bases. There were teams located at Chicksands, Burtonwood, Sculthorse, Altoonbury, High Wycombe, London, Suffolk, and Weathersfield.[16] By 1993, the last year of play for tackle football, only Upper Heyford and Chicksands remained of the original base teams, but they had been joined by Lakeneath, Midenhall, and Alconbury.[17] British teams were part of the European Command’s sport program that sponsored three districts at it height, which included the UK District, the France District, and the Germany District. The Germans were the class of the EC football world, and reportedly ran programs that were the EC equivalent of modern big-time programs in college football. The initial British entry into the USAFE final was the Burtonwood Bullets, who lost to the Rhine Main Rockets in 1951. That game was played in Germany, but the next season, England would have the home field advantage.

Image from: http://www.Britballnow.co.uk

The first American football game at Wembley Stadium was the USAFE final between the Burtonwood Bullets and the Fustenfeldbrook Eagles on 13 December 1952. The Germans once again were too powerful as Fursty defeated Burtonwood 26-7. Around 30,000 attended the game, so the British press paid attention to the game once more, but they were largely as negative as they had been in 1910. The Sunday Graphic headline screamed “It’s Moider” and Graphic reporter Dennis Dunn declared that “It was sheer madness and a sight that made strong men turn pale.” He went on to relate that “A hard-bitten British football (soccer) reporter turned white faced to me and said ‘I have never seen anything like this. These fellows have something.’ I heartily agree. Personally, I do not think it is curable.” In another Graphic story the paper told readers that “At some secret signal, utterly ignoring the ball, the 22 leaped at each other’s throats. A whistle blew and the debris was removed…Stretcher bearers kept carting off the bodies and the score apparently depended on a coroner’s report – Then the final whistle blew and we gave three hearty cheers to the ambulance which had won a fine game.” The Sunday Express piled on calling it “Murder in the Midfield. Reynolds News was a bit more restrained, telling its readers of “Mayhem, Hula and Bands.” The Sunday Pictorial reportedly described the cheerleaders saying that “pretty girls leaped up and down in Maori war dances to stir up the crowd, shouting ‘How do you like your oysters – raw! raw! raw!’”[18]

Sterling Slappey of Stars and Stripes noted some British fans were impressed . He quoted one disgruntled British fan, however, who he described as “a proper cricket type with mustache bristling” that felt the game was “deplorable.” Another terse commenter added “It’s a shame, a complete shame.” Some in the crowd of 25,000 wondered how many fatalities teams suffered after viewing the mayhem on the field, with one commenter declaring that “The battles a bit rough, isn’t it? Do you get many fatalities per game? (11 in 1953, and 12 in 1954[19]) Your American scrum is a beastly place to be.” A BBC announcer “kept insisting,’ ‘You know I’d like this game a lot, really, if I knew what was going on down there.’” Slappey concluded by asserting that even though the game left a “general favorable impression” on the British, the chances for the game taking off there were slim. “But don’t think football will catch on in England. It hardly has a chance. England already has its cricket, rugby, and association football (practically no resemblance to the American kind), and those three are enough for any nation.”[20]

Embed from Getty ImagesProfessional American Football in Great Britain

The Stars and Stripes writer was ultimately incorrect, and the British did begin playing football, but not for another three decades. The catalyst for convincing British athletes that football did not surely lead to death and dismemberment was the debut of Channel 4 in 1982. It offered re-telecasts of NFL games, and carried the Super Bowl. Now an increased number of people in the UK could see the game for themselves, and some liked what they saw.[21]

At the same time, the NFL was beginning to search for fresh markets to introduce their product. Several promoters thought that the world was ready for some football. Those included men such as Tex Schramm of the Dallas Cowboys, who had begun securing international talent when he signed Austrian kicker Toni Fritsch. Schramm was also interested in creating a demand for football, globally, and in Europe in particular.

Another was the American promoter John Marshall, who arranged the first NFL game at Wembley. He brought over the Minnesota Vikings and the St. Louis Cardinals to play an August 6, 1983 game there. The game attracted 32,847 spectators, but Marshall ended up losing £420,000. Once again, some in the British press held forth a less-than favorable opinion of the game. The Sunday Express gave it a thumbs-down saying, “All those endless collisions of outsize flesh and blood… all those baffling hand signals and free-coded rhythm grunts, which only players of their own side could understand… and all those coaches barking orders – to the outsider it was a disorganized mess. A Big Bore!”[22]

Still, the game made a considerable splash, and with the NFL on the television, some Britons were encouraged to try the new game. Rowland Pickering was one of those who were fired-up by what they saw, and he gathered a group of friends who met near Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park. Only two of the young men that appeared that day had ever played football. One was Adam Less, a Canadian living in London, and the other, an American named Lou, who had semi-pro football, according to what Less remembered in a post to the London Ravens historical website.[23] They also had some early help from the Chicksands Chicks of USAFE, who worked with the team and scheduled some early scrimmages with the Ravens. Although the Air Force team reportedly thought the request for a practice game was a “practical joke,” they went ahead with the game that was played at Stamford Bridge on July 9, 1983. The Ravens gave the Chicks more of a game than they had thought, and the Americans only pulled out a win over the upstart British 8-0. A second game was a 38-0 blowout Chicks victory, but the Ravens were on their way.

The first all-British game took place once again at Stamford Bridge, and pitted the Ravens against the Northwich Spartans. The Ravens preparation paid off and they won an easy 48-0 victory in October of 1983. The groundbreaking team quickly looked for new fields to conquer, and played the Paris Castors (Beavers) to a 6-6 tie in the first international game played in England. They followed that up the next year with a 51-0 drubbing of Paris Spartacus, the first French team that began play in 1980. The students became the masters by defeating the Chicks 13-12 in a 1985 game. The gods of history were on the job during the last two games, and someone recorded them, and they are now available on YouTube.[24]

The pace of football in the UK was quickening, and on July 21, 1984, the USFL tested the waters with a match at Wembley. The Philadelphia Stars and Tampa Bay Bandits, owned by actor Burt Reynolds, drew 21,000 spectators to a game won by the Stars, 24-21. Tony Wells, a fan at the game gave an interesting reason for his interest in football when he told a reporter that “American football is a family game …We can take the wife and kids if we want.” He was contrasting this with the atmosphere at soccer games, where one was liable to be tear gassed during the disturbances that sometimes marked the more established sport.[25]

With around twenty teams now playing in England in 1984, the need for organization became apparent. Unfortunately, nobody could agree on what form that organization should take. The fledgling British American Football Federation called for a meeting at the Baden Powell House in London, which ended in more division, and the BAFF retained only seven of the teams there. The others returned to the scene of American help, and held a meeting at Chicksands AFB. This resulted in the formation of the American Football League (UK), with 22 teams signed. There were also other smaller associations, including the UK American Football Association, and the Amateur American Football Conference.[26]

The most powerful teams, including the Ravens, went with the AFL (UK), and the Ravens dominated play. The league final featured their version of the Super Bowl, the Summer Bowl, and in 1985, the Ravens defeated the Streatham Olympians 45-7.[27] In 1986, the championship became the Bud (as in Budweiser) Bowl, then the Coke Bowl. These were joined by the Britbowl in 1987, and this remains the name for the championship game for American football in Britain.[28]

The NFL returned in 1986, when the world champion Chicago Bears played the Dallas Cowboys before 86,000 fans in the first American Bowl at Wembley. The Bears won 17-6, and I remember that one of the best interview lines was provided by Cowboy’s coach Tom Landry, who quipped that the last time he had been in London, he had been taking a break from dropping bombs on Germany.

Embed from Getty ImagesMore significantly, 1986 witnessed the first football game in the UK played by two teams made up completely of female players. In November, the East Coast Sharkettes defeated the Eastbourne Crusaders 30-12 in a game at Bognor Regis. It would be some time before another female game took place, but women would eventually join their male counterparts in playing gridiron tackle football.[29]

In the late 1980s, BAFL went into receivership, and the Budweiser leagues took over. The Bud League featured the top fifteen teams in the National Division, forty-eight in the second Premier Division, and thirty-two more teams in their Division One. This was also the period when British teams began importing North American talent to elevate their game. Bo Hickey of the Fylde Falcons, who played college football for Western Maryland, set the passing record of 3,725 yards in 1988 that still stands.[30]

At the start of the 1990s, Budweiser gave way to Coke, and leadership of British football continued to evolve, and be contested. From 1989 to 2010, the British American Football League held sway, but the British American Football Association finally took control in 2010, and continues to be the primary league.

A new American football league came knocking in 1989, when the Arena Football League played a game in London on November 18, 1989. 12,000 fans came to the London Arena to watch the new version of the game that Jim Foster had created while watching an indoor soccer game. The Detroit Drive defeated the Chicago Bruisers 43-14, and Foster had plans to expand indoor football to the UK, but nothing came of that.[31]

The NFL, in addition to continuing to play American Bowl games in London, also launched an even more ambitious program in 1991. NFL Europe began as the World League of American Football before being renamed as NFL Europe, and then NFL Europa. While it lasted, from 1991 to 2004), the league sponsored two teams from the UK. The London Monarchs was the first to play, and the first UK team to win the World Bowl in its first season of play. They were joined by the Scottish Claymores in 1995, and the northern team also won a World Bowl in 1996. The Claymores also played for the championship in 2000, but fell to the Rhein Fire.

Although the majority of the players in NFLE were Americans, some British players made the rosters, and a few of those made the transition to the NFL. Another few have made the big league without the help of the NFL’s experiment that ceased play in 2004. Probably the most successful player born in Britain was Osi Umenyiora, who played for the New York Giants and Atlanta Falcons during a stellar, but injury plagued career that began in 2003 and culminated in 2015. Umenyiora is currently featured in the NFL Undiscovered video series that explores the difficulty that international players have making the grade in the league.

The British National Team Adopts American Football

Not long after football began in the UK, the British National Team started to contest for the European Championship sponsored by the International Federation of American Football. They earned fourth place in 1987, losing to Finland 38-23 in the third place game. They got their revenge the next two years and defeated the Finns in 1989 and 1991 to win the European Championship by scores of 26-0 and 14-3, respectively. After not fielding a team in 1993 and 1995, the Lions returned to the upper echelon, finishing fourth in 1997 and 2005. For those wishing to cheer on the Lions in international competition, they will be playing the Russian team on September 16 at Sixways Stadium in Worcester. This is the qualifying round for the 2018 European Championship that will be held in Germany. The men’s national flag football team will also be playing this week, when they take part in the IFAF Men’s and Women’s Flag Football World Championship in Miami, Florida.

The UK women’s team has also had considerable success in the latest round of international competition. Their first competition on the European stage was a 5 on 5 friendly game against the Swedish National Team on October 20th, 2013. The British team lost 27-10, but in a rematch playing with full teams for the first time, the GBNT won 26-14 in another friendly match. The female Lions entered the Women’s European Championship for the first time in 2015, and unexpectedly finished second to the Finns after losing 50-12.[32] Women’s 11 on 11 tackle football is relatively new, and the Sapphire Series championship has been held since 2014, with the Birmingham Lions winning the championship every year. BAFA also holds the Opal Series, a 5 on 5 flag football competition for women from October to December each year. Women from the Opal Series teams then can be drafted to play on the Red Diamond or Blue Diamond 11 on 11 teams to play a three flag games for the championship.[33]

After hitting “rock bottom” in 2000, the number of tackle football teams rebounded. There are currently twelve teams in the Premier League, eighteen in Division One, and thirty-four in Division Two. Since the BAFA took over in 2010, London teams have dominated the Premier Division. The London Blitz won the Britbowl from 2010 to 2012, and the London Warriors have been champions since then, winning the last four Britbowls. The women’s division has at least ten teams, based on the home teams of the national team, and British University Football League, which is part of BAFA, had eighty teams for the 2015-2016 season. The university teams began play in 2007-2008, and since then, the Birmingham Lions have been the class of the league, winning four championships, including last season’s, in nine years.[34]

Gridiron football may be the American national game, but the rest of the world is beginning to discover the joy of visiting violence on opposing players. The game debuted in the UK over one hundred years ago, but it has only been a little over thirty years since the game took root among the indigenous population. Since then, men and women, students and adults, both young and old have joined the huddle. Appreciation for the game continues to grow, through the push of the NFL and the pull of homegrown players and fans. Whether the NFL ever locates a team in London, the game has begun to sink roots. While it still exists on the margins of soccer and rugby, more and more Brits are answering in the affirmative when asked if they are ready for some football.

Postscript: the British men’s and women’s national teams had a successful weekend in international competition between 15 and 18 September. The GB Lions Men’s National Team defeated both Russia and the Czech Republic, and the Women’s National Team won a friendly match against Spain.

Russ Crawford is an Associate Professor of History at Ohio Northern University in Ada, Ohio. His area of specialty is sport history, with an evolving focus on nontraditional practitioners of gridiron football. Along with several chapters on sport history, he has published two books. Le Football: The History of American Football in France was recently published by the University of Nebraska Press in August 2016. His first book, The Use of Sport to Promote the American Way of Life During the Cold War: Cultural Propaganda, 1946-1963, was published by the Edwin Mellen Press in 2008.

Notes:

[1] “A history of American Football at Wembley,” Wembley, September 24, 2013 http://www.wembleystadium.com/Press/Press-Releases/2013/9/A-History-Of-American-Football-At-Wembley.aspx (Accessed 28 August 28, 2016)

[2] Robert Booth, “Playing the long game: is the NFL finally about to take off in Britain?” The Guardian, October 25, 2015 https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2015/oct/25/nfl-britain-buffalo-bills-jacksonville-jaguars (Accessed 28 August 2016)

[3] “A history of American Football at Wembley”

[4] Russ Crawford, Le Football: The History of American Football in France, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016, 3

[5] See Wanda Ellen Wakefield, Playing to Win: Sports and the American Military, 1898-1945, Albany: SUNY Press, 1997

[6] “The early years of football in the UK,” BritballNow, 2014 http://www.britballnow.co.uk/history-index/complete-history-of-the/the-early-years-of-football/ (Accessed 28 August 28, 2016)

[7] Ernest Prater, “American Football at the Crystal Palace: Charging a Passage for the Man With the Ball,” The Graphic, December 1910 http://www.abebooks.co.uk/AMERICAN-FOOTBALL-CRYSTAL-PALACE-CHARGING-PASSAGE/11585986118/bd#&gid=1&pid=1 (Accessed 28 August 28, 2016)

[8] “Football in its Most Dangerous Form: An American Footballer Armoured for the Game,” The Illustrated London News, November 26, 1910, 1

[9] “8,000 Irish Fans Puzzled by U.S. Football Game,” Stars and Stripes, November 16, 1942, 4

[10] Yukoner, “USA vs Canada Coffee and Tea Bowls 1944,” Riderfans, http://www.riderfans.com/forum/showthread.php?114041-USA-vs-Canada-Coffee-and-Tea-Bowls-1944 (Accessed 28 August 28, 2016)

[11] Simon Day, “Part 4: WWII – Tea Time in London,” The History of the NFL in the UK, February 27, 2013 https://thenflintheuk.wordpress.com/2013/02/27/part-4-wwii-tea-time-in-london/ (Accessed 28 August 28, 2016)

[12] Gene Graff, “Blues Blank Canadians, 18-0,” Stars and Stripes, March 20, 1944, 5

[13] Ray Lee, “Shuttle-Raders Sink Navy Lions, 20-0,” Stars and Stripes, November 13, 1944, 7

[14] John Wentworth, “Warriors Overcome Shuttle-Raders, 13-0, Stars and Stripes, January 1, 1945, 7

[15] Crawford, Le Football, 61

[16] “Conference Standings,” Stars and Stripes, September 17, 1959, 21

[17] “USAFE standings, results,” Stars and Stripes, October 16, 1993, 29

[18] “’It’s Moider,’London Cries at AF Football Game,” Stars and Stripes, December 15, 1952, 1

[19] United Press International, “Grid Deaths Show Sharp Drop in 1st Half of Season,” Stars and Stripes, November 8, 1955, 20

[20] Sterling Slappey, “’Jolly Good’ Say British of Yank Football,” Stars and Stripes, December 15, 1952, 9

[21] “The early years of football in the UK,”

[22] McKillop, “The NFL’s First Game in London” Football Geography, http://www.footballgeography.com/the-nfls-first-game-in-london/ (Accessed 29 August 29, 2016)

[23] Adam Less, “London Ravens History,” BritballNow, http://www.britballnow.co.uk/History/Ravens/Early%20days.htm (Accessed 29 August 29, 2016)

[24] “London Ravens History,” Britball Now, http://www.britballnow.co.uk/History/Ravens/History.htm (Accessed 29 August 29, 2016)

[25] “When Tampa Bay Football came to London,” BucPower, http://www.bucpower.com/crawford29.html (Accessed 14 September 14, 2016)

[26] Alan Needham, Football in the United Kingdom, Coffin Corner, http://profootballresearchers.com/archives/Website_Files/Coffin_Corner/08-An-03.pdf (Accessed 18 September 18, 2016)

[27] Ibid

[28] British Champions, http://www.britballnow.co.uk/History/Championslist.html

[29] “1983-1987 – boom time,” Britball Now, http://www.britballnow.co.uk/history-index/complete-history-of-the/1983-to-1987—boom-time/ (Accessed 18 September 2016)

[30] “1988 to 1991 – money continues to pour into the game,” Britball Now, http://www.britballnow.co.uk/history-index/complete-history-of-the/1988-to-1991—money-contin/ (Accessed on 18 September 18, 2016)

[31] Interview with Jim Foster, conducted by Russ Crawford, Ada, OH (via telephone) 15 September 2012

[32] “Teams,” SAJL, http://www.sajl.fi/maajoukkueet/ (Accessed 13 September 2015)

[33] “Women’s Football,” British American Football Association, http://www.britishamericanfootball.org/clubs-and-competitions/women%E2%80%99s-football#.V97jOSgrKUk (Accessed on 18 September 18, 2016)

[34] “About Us,” British American Football Association http://britishamericanfootball.org/aboutus.aspx (Accessed on 18 September 18, 2016)

Interesting read. I noticed you mention Belfast, Northern Irealand and I believe a game was also played in Dublin (Republic of Ireland – so not in the UK) at around the same time as well as a game between two US warships at Swansea, Wales in I think 1944. I’ve tried searching for a photo of the programme which I’ve previously seen on the internet to post here. It should also be pointed out the American Football has been played at UK universities since 1986. Here is a post I’ve written about the game in the UK https://newsattwm.wordpress.com/2014/08/11/britains-american-football-warriors/

LikeLike

Pingback: Review of Touchdown in Europe | Sport in American History

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History