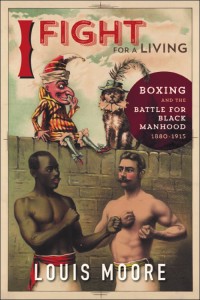

Moore, Louis. I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood, 1880-1915. Sport and Society Series. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017. Pp240. Notes, index, images. $27.95 (paper).

Reviewed by Andrew R.M. Smith

My favorite story about Sam Langford involves a large wager and a good size mule. Some white men bet the notable prize fighter that he couldn’t knock out a beast of burden. Langford took the challenge, feinted with his right, plowed a left hook into the midsection of the mule, and watched it fall over. No ten count required.

Old stories like these should engender new questions. Most obviously, why feint a mule? Next, what (if any) elements of this anecdote are true? In both cases, the answer doesn’t really matter. The aura around black prize fighters at the turn of the twentieth century is just as important as the verified and documented records of the ring. For historians, maybe more so. Lionizing and demonizing African American boxers ebbed and flowed depending on the publication and perception of its readership in Jim Crow America. In I Fight for a Living, Louis Moore goes beyond the headlines to not just shine light on forgotten fighters like Langford and resurrect lost ones such as Henry Woodson, C.A.C. Smith, Billy Wilson or McHenry Johnson, but explain their meaning in all the complexity of the fin de siècle.

Courtesy University of Illinois Press

Langford is one of the better-known subjects in I Fight for a Living, along with Joe Gans, Sam McVey, Joe Jeannette, Peter Jackson and the first recognized black heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson. Those familiar with the history of race in the prize ring, at least, will recognize these names. But in a brisk 172 pages of text Moore gives as much attention to many lesser-known gems of the fight game including one “Black Diamond,” a “Black Pearl,” and multiple “Black Stars.”

This broad-based approach is purposeful and powerful. Moore writes about these participants in a highly individualized sport as a “collective group” of working-class African Americans (p. 21). It provides a bottom-up history of black boxers navigating social class in the context of Reconstruction, industrialization, and migration; gender during America’s transition away from Victorian mores of masculinity; and race in a shifting space from Emancipation to Jim Crow. In readable prose liberally interspersed with fight scenes, Moore admirably demonstrates the pursuit of intersectionality in sport history.

The crux of the study is to conceptualize boxing as work, not just recreation or sport. From there, Moore lays out a tripartite thesis. He argues that prize fighting functioned as a “surrogate to the racist job market” for black men. African Americans who chose that line of work then also chose to perform their masculinity in ways that adhered either to the sporting culture (“Good Fellows”) or Victorian middle-class values (“Refined Gentlemen”)—with an option to alternate that performance as they desired. Finally, those who succeeded in the ring “shattered the myth of black inferiority” particularly when they defeated white opponents (p. 11). However, the threat to racialized mythos incurred the wrath of white media which resulted in the dehumanizing of black athletes or diminishing of their achievement in the press. Scientific racism cried foul when Social Darwinism couldn’t toe the scratch.

Moore reminds us that the black press, which grew significantly in the U.S. during this time period, did not always champion African American prize fighters either. His extensive research of newspapers and magazines targeting African American readers reveals ambivalence at best. While they sometimes extolled boxing victories as part of their effort to combat white racism, these vehicles were also dominated by the black middle-class. They regularly denounced working-class African Americans who participated in or consumed low culture like prize fighting for fear that it undermined arguments for “suitability” and ultimately full citizenship (18).

This debate occurred as boxing underwent a significant change as well. When the “Queensbury Rules” overpowered the London Prize Ring or “Broughton Rules” prize fights increasingly became gloved contests with timed rounds that were considerably more palatable to middle-class sensibilities.

Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

The business of boxing shifted in accordance, and the dominance of wealthy white “backers”—like the aristocratic patrons of British pugilism—gave way to a more regulated, complex, and systemically racist sport governed by predominantly white segregated athletic clubs and negotiated by majority white managers. It paralleled a transition from the overt racism of a slave-based planation economy to the tangled web of sharecropping arrangements.

Not only are the characters in I Fight for a Living caught between the external and internal conflicts of white and black media, they also reflected inter- and intra-racial political conflict. Winning fights and earning large purses—some easily ten-times more than the average annual salary of a black industrial worker—could be construed as evidence that African Americans were “fit” to succeed elsewhere in the economy. Their actions outside the ring, whether they performed as Good Fellows or Refined Gentlemen, could represent aspirations of gradual integration or rapid social equality. They fit squarely in the debates between Booker T. Washington and WEB DuBois over the best path to equality while navigating the obstacles placed by Progressive era politicians, many of whom sought to avoid such issues by simply banning interracial boxing matches.

In retrospect, a mule wasn’t a very difficult target for Sam Langford. It stood pretty still.

For an Afro-Canadian who freely migrated into, around, and outside of the United States in search of a good fight and a big purse, that was rare. Langford, like the many black boxers Moore follows, had to navigate moving goalposts for race, class, and gender in a nation experiencing drastic changes in each. He was, literally and figuratively, always on the move.

That feeling of constant motion pervades the pages. A comprehensive mix of primary and second source research integrated into vivid writing reflect all the passion of a second book. It is organized more thematically than chronologically which may escape the grasp of undergraduate students. But it could prove to be essential reading for graduate students in the field as part of a historiographical arc from earlier work on sport generally or boxing specifically and social class at the turn of the 20th century. It could also function as a sports-centric crossover for scholars of race and labor history, masculinity studies, or the cultural antecedents to the Harlem Renaissance. Regardless of taste, Lou Moore gives us a lot to chew on in I Fight for a Living.

Andrew R.M. Smith is Assistant Professor of Sport Management and History at Nichols College in Dudley, MA. He does not condone violence against draught animals.