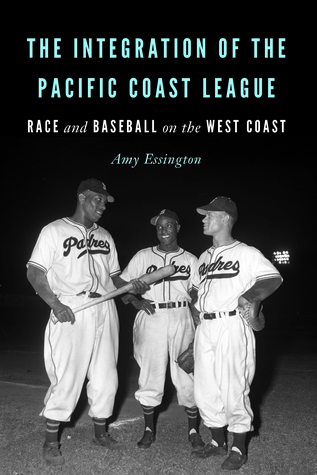

Essington, Amy. The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018. Pp. 162. Afterword, appendix, notes, and bibliography. $19.95 paperback.

Reviewed by Bob D’Angelo

Jackie Robinson’s heroic struggle in breaking the color line in the modern era of major league baseball has been told extensively, and justifiably so. Equally important, however, is the story of the desegregation of baseball at the minor-league level. Amy Essington, an instructor in the history department at California State University, Fullerton, fills the void in The Integration of the Pacific Coast League: Race and Baseball on the West Coast.

University of Nebraska Press, 2018.

The book is a natural progression from Essington’s dissertation at Claremont Graduate University, “Segregation, Race and Baseball in the Pacific Coast States: The Desegregation of the Pacific Coast League.” In her book, Essington explores relatively uncharted territory because records are so scarce. She argues that the story of integration goes beyond the major leagues, and while baseball should recognize Robinson’s achievements, it should look beyond one pioneer. In essence, Essington attempts to “expand the historical focus from one to many.” (p. 3) The Pacific Coast League (PCL) enjoyed open league status and discussions about adding it as a third major league remained a lively subject until the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants moved to California in 1958.

The PCL was not the first minor league to integrate, but by 1952 it had an African American on each of its eight franchises, which was far ahead of any other baseball league. Major league owners certainly dragged their feet, with the Boston Red Sox becoming the final team to integrate when it added Elijah “Pumpsie” Green to their roster in 1959.

Essington’s prose lacks the warmth and sentimental tone that Gaylon H. White used in Singles and Smiles, his biography about one of the PCL’s racial pioneers, Artie Wilson. Her writing is straightforward, earnest and almost clinical at times. What shines through in this work, however, is Essington’s effort to construct the racial history of the Pacific Coast League from scratch. This took some digging. Essington had to plumb the sparse records of PCL franchises, their cities’ historical societies, newspaper articles, oral histories and scrapbooks. She also interviewed the widow and nephew of John Ritchey, the first player to integrate the PCL when he joined the San Diego Padres in 1948.

Essington’s persistence yields historical dividends. Her chapters include sketches about Ritchey, Wilson, Luke Easter and Minnie Minoso. Wilson had the distinction of integrating two PCL franchises, the Oakland Oaks in 1949 and the Seattle Rainiers in 1952 (along with Bob Boyd). An interview Essington recounts — San Diego owner Bill Starr spoke to the Chicago Defender in 1950 — is instructive to the mindset of West Coast baseball. “Of course we were aware of the implications. But the main thing is: we were looking for good players.” (p. 61) Essington rightly observes that Starr was able to see past a player’s racial makeup and focus instead on his talent. And from an economic standpoint, introducing black players also tapped into a new market as African American baseball fans began attending PCL games with more regularity.

Essington also provides an insightful background on the racial makeup of the PCL before World War II, beginning with Jimmy Claxton, who was considered a “Native American” by the Oakland Oaks when he pitched one game in May 1916. Tidbits about players of Asian, Chinese, Hispanic and Native American heritage are also included, and Essington includes an appendix listing the players in those categories.

An interesting aside, which unfortunately Essington did not explore more fully, was the case of Lefty O’Doul. The Seals manager was a fixture in the Pacific Coast League and was revered in Japan, where he was considered influential in spreading baseball’s popularity in the Far East before and particularly after World War II. She gives the reader a taste in two pages, but it seemed as if there was more to the story. She does reference an interview Barney Serrell gave to Barry Mednick a few years before his death in 1996, where the former player said O’Doul “was a racist and didn’t try to hide his feelings.” (p. 98) But perhaps interviews with the families of Frank Barnes (who died in 2014) and Bob Thurman (who died in 1998) might have shed more light. Overall, the light handling of O’Doul doesn’t detract from the book’s effectiveness, and in the relative history of the PCL it is probably a minor blip on the radar.

Jackie Robinson was a trailblazer in integrating major league baseball, but as Essington shows, there were pioneers at the minor-league level who also blazed a path for a future generation of African American players. The Pacific Coast League integrated quickly and was ages ahead of other areas of the country. Essington’s book provides readers with a concise, useful examination of that progress.

Bob D’Angelo was a sports journalist and sports copy editor for more than three decades and is currently a digital national content editor for Cox Media Group. He received his master’s degree in history from Southern New Hampshire University in May 2018. He is the author of Never Fear: The Life & Times of Forest K. Ferguson Jr. (2015), reviews books on his blog, Bob D’Angelo’s Books & Blogs, and hosts a sports podcast channel on the New Books Network.