On May 25-27, 1973, scholars gathered at Ohio State University’s Center for Tomorrow for the first North American Society for Sport History (NASSH) convention. The inaugural group was largely comprised of scholars with physical education backgrounds and an interest in sport history. Not surprisingly then, the first convention showcased thirty papers with ancient Greek athletics, baseball, historiography, and physical education as the most frequently discussed topics.

Over forty years later, NASSH has grown in membership and the convention, hosted by the Georgia Institute of Technology, has diversified in topics discussed. The pre-conference and post-conference workshops, paper themes, and attendees’ backgrounds all illustrate the expanded nature of the field. With over 165 papers, 49 sessions, two keynote addresses, and one graduate student essay, NASSH once again proved to be a thriving community focused on a plethora of sport-related topics.

As the Sport in American History blog did last year, contributors review some of the scholarship presented, addresses given, and awards honored in this post. It is not possible to provide a comprehensive account of the conference; therefore, in what follows, we offer summaries and make connections between several of the presentations. Topics that emerged throughout the three-day convention include: business and media; Cold War Sport; doping and anti-doping; labor and legal issues; methods of writing; narratives of the national pastime; Olympics, Olympic committees, and international sport; race and racism; sex and gender; and teaching and technology.

Due to concurrent sessions, we inevitably missed important presentations and thought-provoking conversations. As such, we encourage other conference attendees to provide more insights and summaries in the comments section at the end of this post

Business and Media

Several scholars explored the business side of sport history. In his paper, Manchester professor Wray Vamplew made an impassioned argument for the importance of business to sport history. He looked again at Stephen Hardy’s 1986 journal article, “Entrepreneurs, Organizations, and the Sport Marketplace: Subjects in Search of Historians,” noting that, in his opinion, the article should have inspired far more articles on sport business than it has in the subsequent thirty years. (It, perhaps, should still be pointed out that while many feel that sport historians have not given the business history of sport its deserved attention, on Google, Hardy’s 1986 article is one of the most cited of the Journal of Sport History). Vamplew built on Hardy’s notion of sports entrepreneurs and argued that there are a wide variety of entrepreneurs and that many were not primarily motivated by profit. Utilizing the language of a trained economist, he classified entrepreneurs by those motivated by: Direct Income, Indirect Income, Psychic Income, and Not-For-Profit entrepreneurs. Vamplew noted that so called “Dark Entrepreneurs,” who often used sport as part of illicit schemes, were just as much an “entrepreneur” as successful, above-board entrepreneurs as were promoters who set up sporting events or practices for non-profit reasons to promote a cause. He concluded by arguing that there were a wide range of entrepreneurs and that historians should be as interested in studying those that were financial or other types of failures as the Mark Cuban’s of the world. Vamplew suggested that in many cases, the failures had larger impacts on the actual practices of sport than the successes.

Dilwyn Porter, from De Montfort University, examined the 1926 soccer (football) competitions and sport tourism trips between residents of Worcester in the United Kingdom and Worcester, Massachusetts. During the mid-1920s, Worcester US and Worcester UK held exchange football tours with the intention of promoting “Anglo-American Understanding.” The tours were a product of the Worcestershire Summer Fellowship, an off-shoot of World War I-era British-American Fellowship of 1917, which existed to extend hospitality to United States troops. In his analysis of period papers, Porter noted that journalists covering the trips often emphasized sport less than the other activities. And, at least in one case, a British writer noted that the “American players were a little too vigorous for their British hosts.”

ABC broadcaster Alex Karras. Courtsey of Wikimedia Commons.

Scholars also discussed how the media intersect with popular sports in the United States. University of Iowa professor Travis Vogan focused on sports media by examining the racial politics of Monday Night Football. He explained how some of the racial dimensions of the show’s sports coverage set the standard for other media productions, particularly ABC. For example, the show cut former player Fred Williamson, a black man, after he flaunted his sexuality, and hired former player Alex Karras, a white man, even though he was known to have issues with gambling.

Ted Geltner, from Valdosta State University, presented on longtime American sportswriter Jim Murray. He detailed how Murray developed his skills as a storyteller at the Los Angeles Examiner in his early 20s before covering Hollywood for Time Magazine. Yet, it was Murray’s Life magazine article describing his hatred for the New York Yankees that launched his sportswriting career. Then, after writing for the fledgling Sports Illustrated, Murray switched to the LA Times, where he remained for nearly forty years.

Cold War Sport

Cold War confrontations also peppered the conference program. Several scholars explored the ways in which sport became a propaganda tool during this time period. Russ Crawford, from Ohio Northern University, explored American football in the 1952-1967 NATO era in France. He explained how the US Department of Defense encouraged–and financially supported–the sport abroad to create a “small slice of American life” in different countries. According to Crawford, the sporting efforts served two strategic purposes: to encourage positive morale for military personnel and promote a positive image of America during the Cold War. Likewise, Sam Schelfhout, from the University of Texas, Austin, examined the political impact of the US weightlifting team’s 1955 goodwill tour to Afghanistan, Burma, India, and Iraq. Although received positively in the Middle East, the seven lifters did not build substantial, long-lasting diplomatic relationships.

Furthermore, Nevada Cooke, from Western University, argued that as faith in America society and American sport weakened–due to the Vietnam War, Watergate, and defeat to Soviets in the Olympic medal count–the USOC grappled with bringing sport under federal control. However, fears that this entailed government-funded amateurism, parallel to the communist model of state-sponsored sport, convinced the USOC to instead address the problems with the President’s Commission on Olympic Sports. Brad Congelio, of Keystone College, explained why US President Ronald Reagan agreed to three seemingly outrageous Soviet demands for the 1984 LA Games: permission for Aeroflot flights to land at LA airport; the docking of a USSR ship in Long Beach Harbor to serve as a Soviet Olympic Village; and unprecedented security on site, paid for by the USOC. Congelio argued that Reagan acquiesced in order to strengthen the image of the United States. In doing so, he could show the world that the United States was more amiable than its Cold War counterpart.

US delegation during the opening ceremony for the 1984 Summer Olympics. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Others presented counter-narratives to the commonplace “East vs. West” storyline. Chris Elzey, from George Mason University, highlighted the collegiality of the American and Soviet athletes during the 1962 USA-USSR track meet at Stanford University. In contrast to the 1958 event where Cold War hostilities proved omnipresent, the 1962 forum fostered mutual respect and friendliness. Likewise, Dennis Gildea, a Springfield College professor, described the writings of Millard Lampell as counter to typical Cold War era books. In his novel The Hero, Lampell showcased class divisions, critiqued the commercialization of football, and insinuated the exploitation of student athletes. However, when tasked with producing a screenplay for The Hero, he changed the final scene from one of ambiguity to a happy ending, in line with contemporary Hollywood norms.

Finally, Penn State’s Tom Rorke detailed the implications of the Cold War on US sport policy. He showed how the Cold War “Muscle Gap” rhetoric was deployed in the campaign against the AAU’s control of American Olympic athletes in the 1960s. Rorke contended that the political momentum built by the sports-federation movement in the 60s culminated in the Amateur Sports Act of 1978, and, further, that we should pay more attention to the influence of individuals who pushed for those changes.

Doping and Anti-Doping

Doping was another popular topic. John Gleaves and Emmanuel Macedo, both from California State University, Fullerton, presented on the 1966 Tour de France riders’ strike, which was a response to the first ever drug tests in cycling. Their paper discussed how cyclists initially opposed tests and argued that anti-doping controls breached their rights. More specifically, they explained, “the riders who supported the protest . . . felt firmly that their rights as workers had been violated.” However, Tommy Simpson’s death in the 1967 Tour de France pushed these protesters into a murky underworld, unable or unwilling to speak out against anti-doping policies. Daniel Rosenke, of the University of Texas, Austin, chronicled the life of Dr. Robert Kerr and his involvement with doping during the 1980s. Dr. Kerr, a controversial figure in the realm of sports medicine, initially supplied athletes with drugs as way to keep them from securing performance enhancing substances from the black market. He claimed to have helped twenty US athletes earn gold medals in the 1984 Olympics as a result. However, later in life, Kerr became an advocate for anti-doping legislation. Ronsenke’s discussion left the audience questioning what kind of legacy Dr. Kerr deserves.

Finally, Thomas Hunt, also from the University of Texas, Austin, discussed high school football, an important part of Texas culture. In his paper, Hunt analyzed the way in which anti-doping initiatives have failed in the state. The Texas government passed legislation that required random drug testing of high school football players in 2007 and allocated significant finances to curb drug use; however, based on the limited results–only forty positive samples found over the life of the program–Hunt suggested the state funds could be spent in a more productive manner. For example, concussions and heat stroke negatively impact more high school athletes than doping.

Labor and Legal Issues

As questions of labor and the law continue to coalesce in contemporary sport, NASSH members explored the roots of this relationship. For example, Southeast Mississippi State University professor Adam Criblez reframed the historical understanding of the 1976 ABA-NBA merger. While affirming the stylistic impact the ABA had on the NBA, Criblez argued for the merger’s influence on the business of the NBA. Notably, in anticipation of the merger, the NBA removed the reserve clause. This combination of policy and organizational change resulted in the reconfiguration of team-player relationships, particularly by allowing star players to receive higher salaries and encouraging more player-movement between teams. In light of the upcoming expiration of the NBA’s current collective bargaining agreement, Criblez’s presentation provided valuable historical context for thinking about the dynamics of player-team labor relations.

David Sumner, a longtime scholar at Ball State University, shared his re-evaluation of the Wally Butts-Bear Bryant telephone scandal of 1963, which involved the Saturday Evening Post publicly accusing Butts of sharing play information with Bryant. The coaches sued the magazine for libel, with the Supreme Court ruling in their favor. Using his careful analysis of media and legal sources, as well as Alabama’s football strategies, Sumner argued that Butts did share implicating information with Bryant. But more importantly, Sumner’s evidence has the potential to muddy the houndstooth-glazed image of Bryant, thus illustrating the power of detailed, primary source-based research to challenge popular, idealized narratives of sport heroes.

Methods of Writing

Throughout the conference, a number of panels centered on the ways sport historians do sport history. In a session, for example, five scholars discussed their role in an upcoming sport history book, aimed at “popular audiences.” Steve Gietschier from Lindenwood University, who is currently editing the manuscript, argued that writing for popular audiences needs to be both critical and accessible. University of Utah professor Larry Gerlach explained how he tried to make his entry readable and leave the reader with a sense of what historians do. Leslie Heaphy, from Kent State University-Stark, noted that she approached the project by asking the question “If I could take a time machine, what would I want to go out and see what was going on? What are some of the questions I would want to ask? To find out?” Finally, California State University-Stanislaus’ Samuel Regalado saw his chapter as a way to revisit a topic he discussed in his book Viva Baseball! He said that “most people enjoy stories” and that he thus engaged his writing for the book by asking “How do I approach teaching a freshman history course?” Much conversation, especially on the topic of citations, followed the papers.

Toots Short (middle) with Hank Sanicola (left) and Frank Sinatra (right). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In another session, former NASSH president and professor at Skidmore College Dan Nathan challenged narrative writing conventions in his exploration of New York City’s Toots Shor’s, a mid-century Manhattan restaurant and lounge. Rather than arguing for the historical importance of Toots, Nathan illustrated its significance by taking his audience there through first-person narratives, photos, and documentary film clips. Instead of hearing anecdotes about Red Smith conversing with New York’s athletes, the audience vicariously witnessed the legendary sportswriter at work. By situating his audience among those who patronized Toots, Nathan conveyed its status as an important place in the production of narratives of sport history. His exploration also more broadly demonstrated the importance of public places to the creation and popularization of narratives of sport history.

Finally, in a roundtable discussion, four writers debated the particulars of writing about basketball, history, culture, and politics. Flinder Boyd, former player and writer, Santiago Colas, a professor from the University of Michigan, Jack Hamilton, of the University of Virginia, and Alexander Wolff, a writer for Sports Illustrated, all discussed the complexities of writing about the hardcourt game. The four responded to questions from University of Memphis professor Aram Goudsouzian and shared their views on writing, including their favorite authors and books, stories on how they got into writing, and perspectives on the current moment in basketball. They highlighted the importance of smooth and effective writing when dealing with analytics and other data. Good information, they all argued, is only as effective as the writing style.

Narratives of the National Pastime

At the opening of the convention, conference organizer Jan Todd, from the University of Texas, Austin, described the shifting nature of topics at NASSH. In years past, several sessions covered baseball, whereas few on other sports existed. This year, though, a larger number of presenters discussed other sports; baseball still appeared on the docket, albeit in only one complete session. Katherine Walden, from the University of Iowa, examined representations of race and baseball in Vanderbilt yearbooks and student newspapers, from 1893-1912. She showed that a number of racialized depictions of Southern Blackness–produced through the lens of white, middle-class Vanderbilt students and in line with national representations–suggests how a Southern white masculinity was constructed. Many of these depictions used sport rhetoric (“stolen base”) and crude cartoonish drawings to perpetuate racial stereotypes where Black equates to criminality and laziness.

Alvin Dark. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Next, David Barney, an independent scholar and longtime NASSH member, offered what he called a “Familiar Essay.” Barney poetically wove aspects of his own experiences with some moments from Alvin Dark’s life. Although the two never met, Barney shared a few similar life experiences with Dark, a professional baseball player and manager for a number of major league teams throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century. The most prominent similarity was the time Barney’s winding touchdown runs for his junior high football team were compared to Dark’s play only a few years earlier when he played for the area’s high school (“slippery as a Bayou eel”). It was an engaging story about the role of memory, place, and sport in our own lives. The presentation briefly touched on race, but mostly in the role of discussing some of Dark’s racist language as a manager. Finally, the University of Texas, Austin’s, Lauren Osmer examined the depictions of Japanese and Latino baseball players in MLB from 1995 (the year Hideo Nomo won the NL Rookie of the Year Award) until 2009 to determine if and how broader historical racialization narratives were present in contemporary depictions of these players. Her media analysis found that many of the historical racializations of these groups were similarly enacted in contemporary media, with some changes.

Olympics, Olympic Committees, and International Sport

One of the leading discussions of the three-day conference was on the Olympics and international sport. University of Windsor professor Scott Martyn discussed Pierre de Coubertin and his engagement of the five Olympic rings. He explained how Coubertin believed that the rings represented the “five parts of the world” as early as 1914. Yet, almost immediately, the rings started to symbolize the connection between the games and commercialism, which has led to substantial profit for the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Therefore, Martyn explained how the rings mean various things to different people. Some stand by the notion that they represent the “core values” of sport–whatever those may be–while others see them as a commercial component of the games’ marketing scheme. Robert Barney, from Western University, also tackled the controversy of Olympic commercialism, focusing on some of the major players in the debate, such as Avery Brundage, Paul Helms, and John Terence McGovern. Importantly, his presentation included work from the late John Lucas, a sport historian whose work on the Olympic Games has proven influential to the field of sport history.

The Olympic Rings at the 2012 London Summer Olympics. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Moreover, Adam Berg, of Pennsylvania State University, analyzed how Denver first won the bid for the 1976 Olympics, then turned down the hosting opportunity. He discussed how politicians and entrepreneurs maintained pro-growth and pro-development mindsets, which led them to bid for the games on the false assumption of having public support. Eventually, their “disingenuous” proposal and other fabrications resulted in the public’s rejection of the games.

Finally, presenters explored questions of international sporting participation. Tanya Jones, from the California State University, Fullerton, offered her take on South African sport and the Olympic Games. Focusing on the topic of South African Apartheid, her paper detailed the reconciliation between the South African National Olympic Committee and the IOC regarding South Africa’s participation in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. Likewise, Danyel Reiche, from the American University of Beirut, analyzed boycotts, with a specific focus on Lebanon’s sporting boycott of Israel, including its successes and failures.

Race and Racism

Race in the early twentieth century connected three papers in one of the first sessions of the conference. Sarah Jane Eikelberry, of St. Ambrose University, opened with a discussion of the Blue Triangle YWCA in Des Moine, Iowa. She explored the evolution of the efforts of the YWCA to include African American women in their educational efforts. Although segregated, the Blue Diamond served as an example for the eventual integration of the YWCA following World War II. Following Eikelberry, Robert Pruter, of Lewis University, spoke of the Cub-Store Coeds, an African American basketball team that barnstormed across the country from the 1930s to the 1960s. He explained how the squad played any and all opponents across the Midwest for several decades. The ownership of the team shifted several times, as did much of the core group of the team, including Helen “Streamline” Smith, a 6’4” player that was often listed as being a 7’ player. She was typically the public face of the team and she was often pictured standing with her arms spread over the heads of her shorter teammates. Ryan Swanson, of the University of New Mexico, concluded the session by discussing the multitude of sporting events in which Theodore Roosevelt attempted to insert himself. Those included an Olympic dispute, his relationship with the boxer Jack Dempsey, and his effort to prevent Jack Johnson and Jim Jeffries from making money after their 1910 match by selling films of their fight. Swanson related Roosevelt’s insertion of himself into the film debate to his eventual insertion into politics, culminating in his unsuccessful run for president as the head of the Bull Moose Party in 1912.

Ornella Nzindukiyimana, from Western University, discussed the implications of race on early twentieth century Canada. She first discussed the preferred kind of Canadian immigrant during this time period. The government desired permanent settlers comprised of a cohesive social dynamic, in other words, whites. Nzindukiyimana then argued that the Olympics served as an advertising effort for the country to attract immigrants, and provided a stage where nationalism had the potential to overpower racism. Black sprinter Army Howard was therefore featured prominently in Canadian narratives and cartoons surrounding the 1912 games. Howard’s inclusion on the Olympic team seemingly contradicted claims that Blacks were unfit to be Canadian, marking the beginning of a shift. Yet, while his inclusion was important, ultimately winning determined one’s Canadian-ness. This is evident in Howard’s story (as well as later in the century with Ben Johnson). Howard’s inclusion of the team was a sign of potential but his performance was disappointing.

John Price, from Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, analyzed American football player Doug Williams, the first black quarterback to win a Super Bowl. Referred to as the “Jackie Robinson of football” by longtime football coach Eddie Robinson, Williams first became a central figure in the discussion of race when he turned professional in 1977. Then, when he went to the Super Bowl in 1988, he became “a black symbol.” Price ended his analysis with questioning the racialized narratives of Williams in the years following his playing career.

Also centering race in his paper, Nathan Corzine, from Coastal Carolina Community College, connected Atlanta and St. Louis together through narratives of basketball’s Hawks, which moved from St. Louis to Atlanta in 1968. More specifically, he discussed the dreadful symmetry between the two cities in the effort to appeal to white fans. The Hawks repeatedly proved to be the best team in the Western Conference; however, some spectators felt that there were not enough white players on the squad and refused to buy tickets. The expansion NHL Blues further hurt the Hawks because their whiteness attracted fans. In his analysis, Corzine connected St. Louis to ongoing racism related to Ferguson, Missouri, and contemporary racialized incidents in Atlanta, Georgia. Therefore, he explained, “the Hawks remain a compelling metaphor for the dynamics we wrestle with as sport historians everyday.”

Sex and Gender

Issues of sex and gender also appeared throughout the conference. For example, some presenters discussed the impact of gender-based marketing on women’s sport. Mercedes Townsend, of Lawrence College, illustrated the inequitable payments of NBA and WNBA players–the NBA’s 2014 starting rookie salary was $507,366 while the WNBA’s salary cap in 2014 was $87,000–and argued that differences in marketing between the two leagues creates disparate fan demands, which impacts profit. For instance, the New York Liberty marketing campaign shows women in unathletic positions and conveys messages of “family.” In contrast, the New York Knicks materials position all players athletically and underscore the scarcity of available tickets.

Similarly demonstrating the significance of marketing, Kylee Studer, of Houston Baptist University, showed that female participation eclipses male participation at all running distances except marathons. She argued that one reason women may not have overtaken men in the 26.2 mile event is because of how races are marketed. According to the 2015 Road Race Data, three of the biggest half marathon races cater specifically to women: Nike Women’s San Francisco, Disney Princess, and Nike Women’s DC. Contrastingly, no marathons on the top fifteen list cater specifically to women.

In addition, Title IX also surfaced several times throughout the conference. Robin Hardin, Jessica Siegele, Allison Smith, Elizabeth Taylor, and James Bemiller, all from the University of Tennessee, discussed the NCAA’s “emerging sports” for women. In 1992, the NCAA attempted to provide more opportunities by introducing beach volleyball, bowling, ice hockey, rowing, and water polo. Current emerging sports include equestrian, rugby, and triathlon. Taken together, the authors explained, emerging sports added over 12,000 positions for female athletes.

Water Polo, an “emerging sport.”Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

On the flip side, Arizona State University’s Victoria Jackson and University of Iowa’s Diane Williams complicated the celebratory Title IX narrative by presenting overlooked consequences of the law. Jackson used UNC as a case study to demonstrate how a legally-induced commitment to women’s sport allowed athletic directors to treat men’s basketball and football as commercial entities. In other words, the requirement of spending on women’s sport is part of the drive for commercialization of men’s sport. Williams also challenged the progress storyline of Title IX by examining the consequences of the law for women of color. She argued that such liberal reforms are not equipped to address intersectionality; consequently, Title IX has primarily benefitted middle-class white women.

Along with Title IX considerations, papers also addressed issues of femininity. Colleen English, of Pennsylvania State University, Berks, focused on the attention given to “collapsing women” in the 1928 Olympic 800-meter race and the 1984 Olympic marathon. She argued that the myth of “wretched” women in 1928, created by journalists, led to the removal of distance events until 1960. Similarly, in 1984, reporters clamored over the exhausted (37-place-finisher) Gabriella Andersen-Schiess. English explained that while some celebrated her effort, others focused on the “agony of the Swiss girl.” Although no one called for the end of the women’s marathon in the aftermath of Andersen-Schiess’s finish, an overemphasis on health concerns continue to plague women’s sport.

Paulina Rodriguez, of California State, Fullerton, and Katie Taylor, of De Montfort University, also explored femininity restraints. Rodriguez explained how Abbye Stockton fought prevailing gender norms and appealed to the “new breed of female athletes.” Her disregard of norms and encouragement of female strength helped pave the way for women’s weightlifting. As such, US women’s weightlifting grew and made it difficult for the international board to ignore. Taylor similarly centered her piece on a strength sport: American football in the United States, 1880-1950. She showed how newspapers at the turn-of-the twentieth century reported that women were “not mentally able to play football.” Women had (minimal) opportunities to play the sport, but when they did, upholding femininity and female propriety remained imperative. Additional opportunities for women on the American gridiron eventually arose, but moral issues remained an unyielding focus of the press. Tellingly, at midcentury, “powderpuff” games emerged, which urged women to conform to stereotypes and play a more “acceptable” version of the game.

Furthermore, scholars addressed the representation and inclusion of trans athletes in sport. Camille Croteau, from Western University, analyzed media portrayals of transgender athletes, with a particular focus on the cyclist Kristen Worley. Cathryn Lucas, of the University of Iowa, chronicled the institutionalization and medicalization of “transsexuality as a category.” She then delineated a binary spatiality of passing, noting how trans individuals had to be visible for medical attention then transition to being invisible. The ability to “pass” (or not), she explained, is “animated and haunted” by racial history of “passing.”

Tackling another angle of women’s sport, James E. Hunt, of Bond University, analyzed the personal empowerment afforded by sport. She used case studies of Dottie Dorion and Celeste Callahan to demonstrate how sport allowed women to push back boundaries of sporting and social norms. And, addressing the issue of gender in men’s sport, Matthew Klugman, of Victoria University, explored fan narratives. He argued that in the late Victorian era, leaders feared that passion for football spectatorship emasculated men.

Teaching and Technology

With Georgia Tech as the host institution, technology proved to be an important focus of the conference. For example, a panel of scholars discussed teaching sport history in the digital era. First, Andrew R.M. Smith, of Nichols College, discussed teaching sport history online. Although many historians do not get to teach what they research in traditional classrooms, online forums allow more opportunities to do so. Furthermore, these classes typically appeal to students, which can increase enrollments. Therefore, argued Smith, online courses offer a chance to expand teaching and help home institutions. Next, Andrew McGregor, from Purdue University, offered two models on how to transform traditional student essays into larger digital history exhibit projects. These projects serve to build undergraduate portfolios, showcasing the value of history courses, and can also potentially help connect students to local communities if instructors collaborate with local archives or historical societies. Appalachian State University professor Rwany Sibaja finished up the panel by discussing video research projects. Digital storytelling offers students training in new media and pushes them to consider history in different ways. For example, videos require to students to think about the emotion conveyed in multimedia and alternative ways to organize and tell history. Although digital storytelling projects are not a replacement for a traditional essay, they can serve as a teaser and tool for students to organize their ideas before writing longer papers.

Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, in a panel that showcased the work being done at Georgia Tech, four scholars discussed bodies in relation to gender and technology. First, Kera Allen illustrated how the playground movement of the “Progressive Era” developed in Atlanta’s African American community. Earlier scholars of the movement have considered it as an almost exclusively white upper-middle class effort, but Allen contended that African American communities in Atlanta had similar goals, and took similar actions, to healthy play promoters elsewhere. Next, Renee Shelby engaged recent scholarship in the histories of bodies, science, and sexualities in her paper on sexual armor, empowerment, and physical feminism. Shelby’s research demonstrated that while the nineteenth-century records of the Patent Office showed a strong interest in contraptions imagined to prevent masturbation, which are now much rarer, inventors are now imagining an array of anti-rape devices based on those same technologies.

Fittingly for the tech-themed session, Mario Bianchini presented remotely, offering a new interpretation of the East German doping program in the Cold War. Bianchini argued that while previous scholars have proposed that the GDR’s athletics campaign was motivated by political ideologies, we should also see their intense focus on developing a strong science program. Finally, Jennifer Sterling wrapped up the conference with an analysis of the many “new media” tools and platforms used by the New York Times’ “Visualization Lab” for digital content. Freed from the two-dimensional constraints of paper editions, a broad range of interactive graphs and maps can show change over time with depths of detail impossible on paper. This content is now hosted on an exponentially increasing plethora of digital platforms, which may prove unwieldy, but seems to be the future of digital sport media, and will be perhaps, constitute the subject matter for many future NASSH conferences.

Keynotes, Awards, and Conclusion

Each year, noted scholars give honors addresses at the annual conference. This year, Michael Cronin, of Boston College, Dublin, Ireland, gave the Maxwell L. Howell and Reet Howell International Address. His talk, titled “Food,” was a cultural history of meat pies at European football matches. His analysis discussed how fan narratives can be tied to food, particularly the pies, at football stadiums across the continent (and the world). The second keynote, the John R. Betts Honor Address, was given by University of Utah professor Larry Gerlach. His talk, “Confronting History,” discussed the history of racism related to team names and mascots, particularly those of native and indigenous peoples. In particular, he outlined the history of the team name and logo at his home institution, the University of Utah. Finally, NASSH grants one graduate student an award for best essay each year. The 2016 award went to Cat Ariail, from the University of Miami. Her talk, “Between the Boundaries: The Athletic Citizenship Quest of Caroleta Gooden,” analyzed the life and athletic career of track athlete Caroletta Gooden. Her presentation discussed narratives of Pan-Americanism and international competition.

Each year, NASSH also honors individuals who have contributed to the study of sport history. At this year’s conference, NASSH presented two awards. In the first, the “Service to NASSH” award, the organization recognized Wray Vamplew, from Manchester, UK. Vamplew served as editor of the Journal of Sport History from 2007-2012 and won the first NASSH book award with his work Pay Up and Play the Game: Professional Sport in Britain, 1875-1914. The second award, the “Service to Sport History” award, went to University of Iowa professor Susan Birrell. Birrell has been in the field of sport studies for over forty years and was one of the most influential individuals in introducing feminist and cultural studies scholarship to sport history. Not only did she encourage the study of women in sport history, but Birrell also mentored and advised many students who now teach and research across the world.

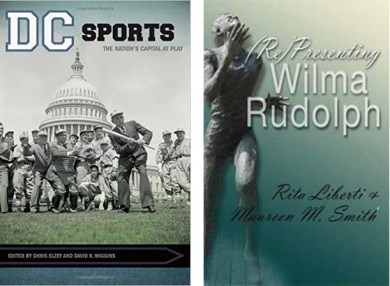

NASSH also announced winners for its book awards. The first award, for best anthology in sport history, went to Chris Elzey and David K. Wiggins for their edited work DC Sports: The Nation’s Capital At Play (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015). Rita Liberti and Maureen Smith won the second award, for best book in sport history, for their (Re)Presenting Wilma Rudolph (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2015).

With over 200 papers and three keynotes, NASSH continues to be a central meeting place for scholars working in the area of sport history. These hundreds of sport-related scholars will gather again, next year, at California State University, Fullerton, for the 2017 NASSH conference. We hope to see you there!

The following people contributed to this post (in alphabetical order):

Cat Ariail, University of Miami

Russ Crawford, Ohio Northern University

Colleen English, Pennsylvania State University, Berks

Matt Hodler, University of Iowa

Andrew D. Linden, Adrian College

Andrew McGregor, Purdue University

Lindsay Parks Pieper, Lynchburg College

John Price, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg

Paulina Rodriguez, California State University, Fullerton

Tom Rorke, Pennsylvania State University

Andrew R.M. Smith, Nichols College

Ari de Wilde, Eastern Connecticut State University

Pingback: Choosing Your Own Adventure: Teaching Sport History Online | Sport in American History

Pingback: Editors’ Choice: Choosing Your Own Adventure: Teaching Sport History Online | Sport in American History

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History

Pingback: NASSH 2017: Call for Summaries | Sport in American History