By Kate Aguilar

“There is power in looking.”

Etan Thomas. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

“By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: ‘Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.’”

~ bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (1992).

On May 20, former NBA player Etan Thomas boarded a crowded train and asked a young White woman with an open seat nearby if he could sit next to her. The 6-foot-10 Black center observed that he “softened” his voice so as not to “frighten her.” The woman said the seat was taken, only to make it available to a young White man minutes later. The result was Thomas confronting her on the bias behind this decision and posting the incident on Facebook. It went viral.

Interestingly, Thomas not only courageously confronted the woman on her prejudice but also proceeded to take a picture of her, which he subsequently posted. He looked back at her, questioning her refusal of the seat to him but not a White man, and did so in a way that was oppositional. He used his gaze to question her own and advertised what he saw – a White woman denying a seat to a Black man – to the world.

Thinking about this incident in the framework of my own dissertation research and the recent documentary on O.J. Simpson, O.J.: Made in America, makes Thomas’ oppositional gaze all the more powerful. Simpson refused to call himself a “Black” athlete to distance himself from the Black athletic revolt of the 1960s. This revolt, in part, pertained to how Black men were required to behave to appeal to White audiences. In the twenty-first century, Black athletes – male athletes, especially – are still called upon to dress and behave in certain ways to make themselves less threatening to White fans. One example is former NBA commissioner David Stern’s 2005 mandatory dress code, of which Thomas was an outspoken critic. In The Washington Post, he wrote, “Maybe the commissioner thinks that if we take off our jewelry, baggy sweat suits, do-rags and T-shirts, the fans will somehow feel more comfortable around us. Or that we won’t be perceived as such a threat… It’s almost as though he is playing to a societal ignorance that has overtaken the mind frame of the masses for generations… What we wear has no bearing on who we are as people. It’s what’s inside that matters.”

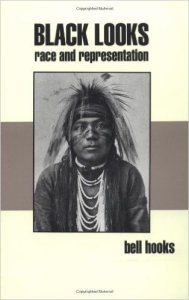

In 1992, cultural critic bell hooks wrote an influential book called Black Looks: Race and Representation. Chapter seven of that work, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” focused on the historical repression of Black peoples’ right to gaze and moments of agency when Black people – especially women – dared to do so regardless of the cost. Recently, I attended a talk from the new police chief of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department. While I am not questioning his desire to serve the city of Indianapolis, I was struck when he described a recent plan to tackle rising crime. The plan included putting a cop in the communities with the most crime 24 hours a day. As a scholar of race, it was difficult not to picture French philosopher Michel Foucault’s panopticon, the image of a circular building with an observation tower. This image underscores the role of surveillance in creating fear and establishing control. The “ever-visible inmate,” Foucault writes, is “the object of information, never a subject in communication.” It was impossible not to shudder considering how 24-hour surveillance would make these largely Black and Latino communities feel. I was later given a glimpse of their response while attending a community meeting where a prominent Black leader stated, “White communities are protected. Black and Latino communities are policed.”

In 1992, cultural critic bell hooks wrote an influential book called Black Looks: Race and Representation. Chapter seven of that work, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” focused on the historical repression of Black peoples’ right to gaze and moments of agency when Black people – especially women – dared to do so regardless of the cost. Recently, I attended a talk from the new police chief of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department. While I am not questioning his desire to serve the city of Indianapolis, I was struck when he described a recent plan to tackle rising crime. The plan included putting a cop in the communities with the most crime 24 hours a day. As a scholar of race, it was difficult not to picture French philosopher Michel Foucault’s panopticon, the image of a circular building with an observation tower. This image underscores the role of surveillance in creating fear and establishing control. The “ever-visible inmate,” Foucault writes, is “the object of information, never a subject in communication.” It was impossible not to shudder considering how 24-hour surveillance would make these largely Black and Latino communities feel. I was later given a glimpse of their response while attending a community meeting where a prominent Black leader stated, “White communities are protected. Black and Latino communities are policed.”

An example of a panopticon. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In this light, Thomas’ post, in which he confronts the woman and turns the lens on her, is both oppositional and transformative. By communicating the questions he asks of her to the world, he asks them of all of us. He asks us to look at her, to see if we see ourselves, and consider how our personal biases determine our actions and the ways in which misperceptions of race and gender operate to inform personal and collective power. In looking back and projecting this gaze outward onto social media, he shows the power of a Black man’s gaze to reframe how we all may see the world.

This image, of course, is not the end of the story. I recently attended a conference where I presented my work on the University of Miami Hurricanes football program of the 1980s, and what popular rhetoric on that team perhaps demonstrates about political and popular narratives of the period. I had the joy of conversing with another scholar who works on Miami, who beautifully captured the purpose behind my work. She observed (and I paraphrase), “What is so interesting about the Hurricanes is that many were oppressed off the field and yet through sport given such power.”

Thomas’ post is of importance because of his role in sport. It went viral because he was a sports star, which in our country makes him a celebrity. His celebrity afforded him the opportunity to speak on a national stage. He is more than just an athlete, as his work attests. He is an author and an activist. Sport afforded him a space to have a public voice; with that voice he has spoken out on several issues and events. Because of his race and gender, he is and has been the object of scrutiny. Sport afforded him an opportunity to look back and force us all to look around in the process.

Thomas, personally, would eventually speak out on the public reception and perception of his post, noting that he was uncomfortable with the clickbait format in which the post took flight. He explained, “I didn’t actually call her racist. All the articles said, ‘Racist white woman,’ and I was like, ‘No, wait, I don’t know if she’s racist or not. I didn’t say that… I was just reporting the facts.’” Compellingly, Thomas then turns his gaze on celebrity culture, challenging us all to further consider how we process information, from the personal – a decision to offer a train seat – to the popular – the ways in which we categorize entire groups and people through labels and, at times, libel. He challenges us to consider how we categorize.

Image from Etan Thomas’ Facebook post on May 20, 2016.

Still, the facts remain. On May 20, Thomas got on a crowded train and asked for a seat. To those of us who work tirelessly to educate others on how race intersects with other identities like gender, class, and sexuality. The ways in which race has been used historically to categorize, oppress, brutalize, and terrorize persons and groups of people, it is heartbreaking to read how a Black man sought to make himself “softer,” smaller, less threatening to gain access to a public space most White persons take for granted. Often overlooked in his oppositional gaze, however, is the image of the White gentleman who was given the seat. Thomas tells of how this man offered the seat to him, clearly embarrassed by the woman’s behavior. The White man’s sheepish look – and the movement of his body away from hers – in the image reminds the audience that not all White people are the same, as are not all Blacks (or Latinos, etc.). Thomas’ oppositional gaze gives this man agency to share his story, to look back. The White man’s body language shows him in opposition to the White woman and how he and Thomas, in this moment, are on the same team. It is a powerful reminder of how we are all interconnected, in look or thought or action.

Ultimately, Thomas’ story is a conversation about surveillance. In a recent “vehement dissent,” Supreme Court Justice Sotomayor spoke about a Fourth Amendment case in Utah regarding “an unlawful traffic stop.” The statistics are clear about the disproportionate treatment of Black and Latino men and women in a legal system that is far from colorblind. In her searing dissent, Justice Sotomayor writes, “By legitimizing the conduct that produces this double consciousness, this case tells everyone, white and black, guilty and innocent, that an officer can verify your legal status at any time. It says that your body is subject to invasion while courts excuse the violation of your rights. It implies that you are not a citizen of a democracy but the subject of a carceral state, just waiting to be cataloged.”

Thomas’ story is worthy of our time and reflection because, if only briefly, he turns this surveillance on its head. He ruminates on how Black men have been oppressed historically, and today. But he also represents how some are able to access power through sport and use their viewpoint to reframe the conversation. It may begin with a game, but it can’t end there. Sotomayor continues, “We must not pretend that the countless people who are routinely targeted by police are ‘isolated.’ They are the canaries in the coal mine whose deaths, civil and literal, warn us that no one can breathe in this atmosphere.” Thomas’ gaze, his courage to ask the questions and to turn the lens back on the woman who denied him access, called out how bias and prejudice put into action impact Black Americans every day. His sport celebrity afforded him a national audience. His story is a significant example of not only why but how the caged bird sings.

Kate Aguilar is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Connecticut. Her dissertation examines Miami and South Florida as critical locations for understanding American conservatism in the 1980s and the national ascendency of the New Right, embodied in Ronald Reagan. It shows how the intersection of race, gender, and sport helped popularize Reagan’s individual story as a national narrative of American exceptionalism, moral and martial power, and heroic White manhood. Using the University of Miami football team of the mid-1980s and their stadium, the Orange Bowl, as case studies, her work deconstructs the common Black/White racial binary of traditional studies of Cold War conservatism and argues that scholars of the Right and post-1968 political realignments must pay attention to the Global South to appreciate how New Right policies and leadership were crafted in response to images of a multiracial, multicultural, multilingual, and multinational urban scene. Kate can be contacted at katelyn.aguilar@uconn.edu.

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History