By Massimo Foglio

During World War II, more than 425,000 German prisoners were housed in 700 camps and a myriad of satellite sub-camps throughout the United States. The agreement with the British government stipulated that the Germans would live and work in the States until the end of the conflict, when they would then eventually be sent home.

Other than the barbed wire and watchtowers, the camps were similar to the training sites the Germans were used to living in before going to the front line of war. But instead of receiving military training, they were assigned to work, especially on the farms where military enlistment had caused a shortage of manpower.

Being former soldiers and sailors of the Third Reich, the Germans were confined to the base during the duration of their stay. Yet, after the Victory Day, they were still captives and certainly under restrictions, though no longer the enemy. Repatriation of the many prisoners would take time. Seven months after the surrender, Camp Stockton and a POW camp at the San Joaquin County Fairgrounds still housed 4,000 Germans awaiting their return home.

Located about 60 miles east of the San Francisco Bay, Stockton is a river port with ships that navigate the San Joaquin River to and from the San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. Today, its population is more than 300,000; in 1946, it was home to 60,000 permanent residents, plus another 4,000 German POWs. Stockton was the biggest logistics and ordnance harbor for the Pacific Theater, and most of the POWs were employed in various handling and transshipment stations.

Colonel Kenneth M. Barager was the commander of the prisoner of war camp, while his colleague, John M. Kiernan Jr., oversaw a branch of the smaller camp at the San Joaquin Fairgrounds. In late 1945, Colonel Barager proposed that the German inmates learn the American game of football. An announcement called for all POWs interested in American Football to apply. A few days later, those who had reported for participation were plucked from their jobs and taken in a stockade where they watched a film and viewed a short presentation about the game. From that day forward, all the “football players” were given a special meal before practice sessions because “football players have to be full of energy and ready to go!”

Barager and Kiernan enlisted two former college players to organize and train the men. Sergeant Ed Tipton of Texas initially gave his team the college-like name Stockton Tech, but this soon gave way to the Barager’s Bears. Sergeant Johnny Polczynski, formerly a receiver for Marquette University, initially referred to his team as the Fairground Aggies, but eventually adopted Kiernan’s Krushers. Shortly thereafter, Coach Tipton taught his men the T-Formation and the Double Wing offense.

Stockton area football teams donated all of the equipment used by the players. At first, only the first-string prisoners received a full set of equipment, including football shoes, while the second stringers had to make do as best they could. “The football shoes were made of very soft leather and provided our feet good, solid support,” Richard Statetzny, Krusher’s left halfback, told historian Ward Carr in an August 2015 interview. “The quality was outstanding. I really took care of them, and I even took them back home with me. When I first got back to Germany I lived with my sister in Dortmund-Lindenhorst and played in the local soccer club there. Nobody else had such top-quality shoes back then. Our three coaches explained the equipment to us. We had items in all sizes there, and everyone found the right fit. Nowadays all football players wear helmets with facemasks. But only one of our first string players got a facemask.” To be sure, the equipment was strange for them at first. But the Germans adapted quickly because it was part of a new sport in which they wanted to be successful.

Before the game between the Bears and the Krushers, the Associated Press ran a few paragraphs about the unique matchup, which appeared in newspapers across the nation. After the last whistle blew, though, only Stockton papers, plus a mention of the score by an Oakland Tribune sports columnist, discussed the game. Years later, Carr interviewed quarterback Lungen, left halfback Statetzny, and other members of the two teams for the German magazine Huddle Verlag. This preserved the legacy of the first American football game between two teams comprised of European players.

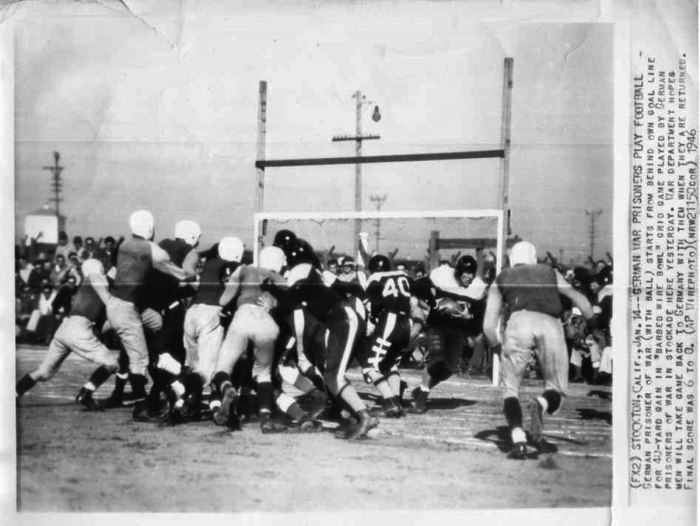

“A press photo of German prisoners of war playing American football at the Stockton Ordnance Depot Prisoner of War Camp. 14 January 1946.” Courtesy of California Military Department Museum.

Port Scope, the Army camp’s paper, provided a detailed description four days after the game. “The only trophy awarded the victors came in the cheers of some 5,000 spectators,” wrote Sgt. Frank Farnham. “When two 22-man squads of German POWs met on the football field, the fundamental desire to win alone more than made up for any lack of the pageantry with which other bowl games greeted the new year, and over 1,000 American spectators left the game convinced that they had been present at the making of history. . . . Two ways of life, two theories of thought, met at the crossroads Sunday on the Depot, and 44 Germans (Nazis by training, traditional believers in the omnipotence of the one and the subservience of the masses) took a forward step on the road where the sign read democracy. . . . There was no dictator on a football field. There were no robots. Instead, there were forty-four men learning the meaning of cooperation, coordination, and fair play.”

A big grandstand for the spectators–which included the military brass, high-level officials with their wives, and the majority of the prisoners in both camps–was erected. Before the football game, two teams of POWs played a soccer game and, when the two football teams came out on the field, the American spectators cheered them on loudly and enthusiastically. During the game, the fans continued to raucously yell, even calling the POWs by name, which they discovered when the coaches yelled instructions to the players. The POWs in attendance, however, were a bit quieter as they did not fully understand the rules of the game.

Kiernan’s Krushers had enough players for two complete teams, which afforded the footballers substitutes when tired. The Barager’s Bears had fewer players on the team and grew fatigued earlier than their opponents. They nevertheless managed to put up a good fight. The Krushers scored a touchdown in the second quarter on a 30-yard run, but it was called back on a holding penalty. The two teams thus went into halftime tied, 0-0.

In the third quarter, the Krushers’ quarterback Hubert Lüngen ran a sneak play for a touchdown, giving the team an edge, but the point after failed. The Bears drove to the ten yard line in the final quarter and seemed ready to strike, but were stopped on fourth down. After a game in which rushing plays dominated, the Krushers came out on top, 6-0.

“Throwing the ball was a problem,” Lüngen later told Carr, “because an egg-shaped ball requires a completely different technique than what I was used to throwing in team handball, and our receivers had some difficulty in catching and holding on to it after it was thrown. Most of the time, we just ran up the middle, and there were a lot of fights that broke out. The line players were the only ones whose helmets included a facemask, and they were the ones who usually started the fights. The referee would intervene and send the offending parties to the locker room before it could degenerate into a brawl.”

After the historic game, players from both teams were invited to the Officers’ Club and introduced individually to the assembled guests by name and position. They were served a feast that was so ample they had enough leftovers to take to their buddies in the stockade. As a memento, all players joined in a big team picture.

With the German prisoners still stuck in camp with little to do while awaiting repatriation (on January 23, 1946, the recreation hall and barracks at the Fairgrounds burned down while the prisoners were away watching a soccer game), it’s no surprise that Barager and his Bears managed to get a rematch.

The teams trained intensely for another four weeks, and faced off again on February 10, 1946, at the Fairground stockade. The game was again preceded by a soccer match between the two stockades, but without as much fanfare as the previous matchup. In the rematch, the Bears, supplemented with more skilled players, played much better, and trounced the Krushers, 20-0.

The 44 prisoners were eventually sent home, along with the other few thousand Stockton prisoners, and dispersed across Germany to their various hometowns. The POWs American football skills soon became just a memory associated with years of captivity in a foreign land. American football would take root across the Atlantic via the POWs, but it would gain traction through the hundreds of thousands of American servicemen who occupied Germany after the war.

Massimo Foglio is an IT employee with an Italian Insurance company. He began playing (American) football in Italy in 1980, and he’s been involved in Italian football leagues as a player, coach, and executive for the last 36 years. He’s a member of the Professional Football Researchers Association. With former PFRA President Mark L Ford, he wrote Touchdown in Europe: How American Football Came to the Old Continent, a book about how American Football developed in Europe.

Pingback: Review of Touchdown in Europe | Sport in American History

Pingback: ICYMI: An Overview of Nearly Everything We Wrote in 2016 | Sport in American History

Pingback: The Barbed Wire Bowl – Zappa's Writing Archive