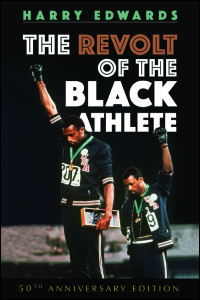

Edwards, Harry. The Revolt of the Black Athlete: 50th Anniversary Edition. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2017. Pp. 232. Appendices, Index. $29.95 hardcover.

Reviewed by Kristy McCray

“There can be no ‘for sale’ sign, no price tag on principles, human dignity, and freedom.” (p. viii)

In 1968, Harry Edwards published The Revolt of the Black Athlete, providing a firsthand look at the activism and rebellion by Black athletes leading up to, and including, the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. The 50th Anniversary Edition features a new dedication, introduction, and afterword, but never have the words written five decades ago felt so timely and relevant. Clocking in at under 250 pages even with new components, this book serves as a teaching tool for sport management, sociology, and history courses, as well as an instructional guide for those seeking to use sport as a tool of the social justice movement. In Edwards’ own words: “Hopefully this book will be read and understood by many people, but particularly by those who control athletics and exert political and economic power in America. For it is the latter who have the power to correct the injustices that beset the American sport scene” (p. 8; emphasis added). After reading this book, I am now considering sending a copy to every major league team owner and big-time athletics director, all of whom should make themselves familiar with Harry Edwards.

University of Illinois, 2017.

For those who even briefly study sport history or social justice movements, the name Harry Edwards should be familiar. In my mind, he is inextricably linked with Tommie Smith and John Carlos as the architect of their raised fists on the 1968 Olympic podium in Mexico City. Thus, I jumped at the chance to review The Revolt of the Black Athlete, particularly in light of a new Gen Ed course I am teaching next year on power and privilege in college sport. As a White woman, I have a lot of reading and exploration to do in order to make the course as reflective as possible of the various injustices in sport. This text was a great start and will definitely be making my course reading list.

In his introduction to the new edition, Edwards provides additional information to flesh out the original text. One would think that in 2017, he would be weary, frustrated, and disheartened to see many of the same issues arising for Black people as they did in 1967-1968. He reminds us of the old adage, “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it,” and explains in threefold why Americans haven’t learned about our country’s injustices and racism. First, people choose to ignore lessons of the past due to fear and demagoguery. Second, we may not be getting the full and complete history, depending on the author and which version of history they are presenting (something I can clearly see firsthand in my life, as the more I consciously and intentionally seek out sources and materials for classes, I realize how much I was taught in my secondary and postsecondary education from the perspectives, authorships, and ideologies of white men).

Lastly, Edwards refers to the notion that, while we are seeing themes of injustice and oppression continue today, we are certainly not repeating history: “Only under almost the unimaginably extraordinary circumstantial consequences of detail and dynamics could there be any possibility that history literally could be ‘repeated’ or ‘relived’” (p. xiii). It is refreshing to think that this self-proclaimed “scholar-activist” can view history in such a way. In the afterword, he compares the revolution by athletes at San Jose State College in the 1960s to the athlete movements of the 21st century, noting that the major difference is social media, “the greatest tool of protest organization in history” (p. 165). There is an undertone of hope throughout this book.

Despite some positive undertones, there are no rose-colored glasses used to review the past. Whether it was genuine editorial oversight, or, in Edwards’ words, “a deliberate effort to editorially undermine the book” (p. xx), the original edition went to press with a variety of errors, ranging from typos to improper citations. He chose to reprint the original manifesto in its complete and flawed form, using this as an opportunity to challenge White supremacy: “Even those Whites who were willing, even eager to work collaboratively with Blacks often came to such task afflicted with sometimes subtly, sometimes brazenly expressed presumption of White superiority – superiority in information, superiority in insight, superiority in judgement, and most certainly superiority in control and power” (p. xxi). Due to these experiences, Edwards notes that for many years, he did not feel true ownership or authorship over this text, and resisted calls for an updated or anniversary edition. However, as we enter what he calls the Fourth Wave of athlete activism, he wanted this book to serve as a history lesson and tool of activism for those working to end oppression through sport.

In the new introduction, Edwards offers his “imperatives of organizing a successful social movement” (p. xiv). First, we should focus on group injustices that are bound by one or more similarities and “mutual connectedness” (p. xv) – now is not the time to focus on the plight of an individual, but rather a group bound by some common oppression (e.g., race, sexual orientation, gender). Second, “I agree with your goals but not with your methods” (p. xv) – in other words, we may have to collaborate with folks doing things differently than we would, as long as we have the same goals in mind. This calls to mind the varying methods of the NFL protests this season: taking a knee, raising a fist, locking arms. Further, the movement needs a strong focus on threatening the ultimate cost-reward outcome of the establishment. This season, many NFL owners were not worried about one-time game boycott, but about the long-term outcomes of a drop in ratings.

Even though Edwards writes that history can never technically be repeated, it is worth reading the first two chapters of this book for the context and understanding of how the 1968 Mexico City Olympics revolt came to happen. Chapter 1 (“The Emergence of the Black Athlete in America”), serves as concise historical overview, and perhaps a stand-alone reading recommendation for Black History Month. It foreshadows the Black athlete as a “commodity” in big time college athletic programs at Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) and the dismal graduation rates of Black athletes, a statistic that remains alarming low and is trotted out by the media every spring while sport fans obsess over their March Madness brackets. More importantly, the chapter provides vivid details of the stories experienced by Black college and professional athletes (more than once, I found myself staring at my pages, open-mouthed and shaking my head).

Many haven’t heard of the historical abuses suffered by Black athletes due to media coverage, the subject of chapter 2 (“Sports and the Mass Media”). This chapter would be an excellent addition to sociology course (for example, a compliment to Jay Coakley’s Sports in Society chapter on media and sports) or sports communication course. Edwards provides strong arguments for why the media has not historically covered racial justice issues in sport, some of which are still relevant today. For example, Edwards writes, “When a white American becomes a journalist, he does not all at once become a citadel of racial and social objectivity” (p. 33), outlining the differences between white reporters who are racist, ignorant, or indifferent. Further, the sports media is a reflection of its (white) editors, owners, and readers/watchers – many of whom believe that politics has no place in sport. Also of interest in this chapter is the history of the Black sports media and its contribution to the oppression of Black athletes. Despite an abrupt ending, the chapter succinctly argues for how media has contributed to racial oppression in sports.

After the background and context of the first two chapters, the following three chapters provide a rich history of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). Edwards uses vivid and powerful prose (“The movement for black liberation dates from the first moment that a black captive chose suicide rather than slavery” [p. 38]) as well as primary documents, such as the United Black Students for Action’s list of demands (pp. 43-44) to outline the rationale for the revolt in detail. Edwards details the actions and meetings taken by himself, as well as other committee members and athletes, to inform athletes of a pending boycott. In fact, many of the original documents, including an “information booklet” printed for athletes (as suggested by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.) are reprinted as appendices.

After an initial and successful boycott of the New York Athletic Club track meet in February 1968, the OPHR set its sights on creating change at the university and college level, as detailed in chapter 4 (“Feeding the Flame”). The OPHR, in conjunction with many campus advocates and student groups, successfully rid some colleges and universities of their racist policies, procedures, and people (i.e., athletic directors, coaching staff). “All in all, black athletes and students revolted on 37 major college campuses during the 1967-1968 academic year [and] athletics was the main lever used to pry overdue changes from white-oriented college administrators and athletic departments” (p. 74). A number of these revolts are either detailed in chapter 4 or briefly outlined in the appendices.

The OPHR (all volunteers, with little-to-no funding, as we are constantly reminded by Edwards) worked with more than half of these schools, even as it worked with professional athletes and prepared to boycott the 1968 Olympics. An impressive feat of activism, but after reading how the Olympic boycott in Mexico City fell through, one wonders if perhaps the focus of the OPHR should have remained on, perhaps, the Olympics. For those of us who are casual historians of sport, we may know or remember little of the movement that led to the black-leather-clad raised fists of 1968. Chapter 5 (“Mexico City, 1968”) is the remedy for that knowledge gap. As the Olympics grew closer, many athletes, essentially, changed their mind at the prospect of a boycott.

Edwards deserves credit for his even-handed approach to this delicate topic. In the end, “it was decided that each athlete would determine and carry out his own ‘thing,’ preferably focusing around the victory stand ceremonies…The results of this new strategy, devised for the most part by the athletes themselves, were no less than revolutionary in impact” (pp. 84-85). One may argue that, 50 years later, all that we remember is the striking image of John Carlos and Tommie Smith on the podium, but some of the impacts were indeed immediately effective. He follows up in the sixth chapter (“The Future Direction of the Revolt”) with a call to Black athletes for “determination, sacrifice, and courage to do whatever is necessary to remove oppression from our backs” (p. 97).

Edwards’ words from 1968 still ring true in 2018. There are so many relevant aspects of this book to current social justice issues, from the #MeToo movement to end sexual harassment and sexual assault to the NFL Players Coalition formed to address issues of racial injustice. I have worked in and around athletics for more than 10 years. When Edwards would describe the (racial) epithets and insults he would hear so often that he claimed “I heard but didn’t hear them” (p. xxvi), I found myself nodding my head and thinking, “Me, too” in relation to sexist remarks or sexual harassment in the workplace. In referring to the revolutionary work that must still be done, he quoted James Baldwin: “To be Black and aware in America is to live in a constant state of rage!” (p. xxv), reminding me of the accusations hurled my way of being an angry feminist. My usual retort is not that I’m an angry feminist, I’m a furious one. And Black athletes still have a reason to be furious, too.

In the preface, as rationale for the revolt, Edwards outlines some of the disparities facing Black athletes. While some may not resonate as strongly in 2018 (e.g., a ban by college coaches on interracial dating), others feel eerily fresh: “At the end of their athletic career, black athletes do not become congressmen…neither does the black athlete cash in on the thousands of dollars to be had from endorsements…all his clippings, records, and photographs will not qualify him for a good job” (pp. 6-7). While Kevin Johnson, former NBA player-turned-Sacramento-mayor comes to mind, many retired athletes are either humbly starting their own small businesses or going broke – but few are catapulting their athletic careers into business success as obviously as Magic Johnson or Michael Jordan.

Even more relevant as Super Bowl LII approaches is a reflection on this season’s protests in the NFL. There continues to be those in America (expressed via presidential Tweet) who believe that Black athletes need to shut their mouths and stand proudly for the flag – they are being paid handsomely, more than the “Average Joe” watching the NFL each Sunday, to play the sport they love and not be advocates of social justice. Edwards and his fellow activists pushed back against the same sentiment in 1967, and he explains that his main goals were to “fearlessly, even stridently challenge and demonstrably prove the fallacy of prevailing definitions portraying the character of race relations in American sport, to establish as unimpeachable fact that Negroes had no more ‘made it’ in sport than any other sector of American society and, therefore, that Black athletes had the same obligation to fight for change as Black people in other arenas of American life” (p. xxx). Many NFL players are taking that challenge seriously, such as Philadelphia Eagles safety Malcolm Jenkins and others involved in the newly-formed Players Coalition.

An advertisement for a recent event organized by the Players Coalition.

And lastly, we wouldn’t be having this conversation about racial injustice in the NFL if not for Colin Kaepernick. Edwards noted that journalists “paid scant attention to the institutionalized conditions that precipitated and drove the movement” (p. x). He was referring to the conditions that led to the 1967-1968 revolts, but this could also be said for many media members’ reactions in relation to both Kaepernick’s original protest, as well as the actions of many other NFL players this season.

Ultimately, this book serves as a teaching tool for the history of race and White supremacy in American sport. But more importantly, it is a playbook for how to change institutional and uncorrected injustices in society through sport. Fifty years later, it’s time to revolutionize the game.

Kristy McCray is an Assistant Professor of Sport Management at Otterbein University in Westerville, OH. She can be reached at kmccray@otterbein.edu or you can follow her sporadic Twitter usage: @KristyMcCray.